It was 2004, and my first year marlin fishing as a mate. I wasn’t just new; I was brand-new. Capt. George Beck was on the wheel of the 58-foot Viking Freebie, and Capt. David Withers was guiding me in the pit. I was looking forward to learning from them. What could possibly go wrong? I asked myself. I was in good hands.

We were fishing the famed North Drop in the Virgin Islands when I got the call to put on the big-boy gloves. Everything was going great that season, and I was ready to wire my 10th-ever blue marlin. It was a graceful, solid fish, doing everything it was supposed to do; Beck called her 450. I had a double wrap in my back hand and a single wrap in the front. As I peered over the rail, I saw that the hook was lodged in her top jaw. I remember thinking: I could take two more wraps with my front hand and then dump my back hand, leaving one hand free to get the hook out. It’s a no-brainer, and I’ll be a superstar. I was wrong.

As I went for the additional two wraps with my front hand, the fish turned on me. A couple of aggressive swipes of that 4-foot tail, and suddenly, my feet were lifted off the deck. The Mustad 7731 10/0 straightened out like an arrow, and I found myself flat on my back, handcuffed in leader material. My heart was in my throat, and I was shaking uncontrollably: I almost got pulled over! I asked Withers to cut me out, but he refused. “Get yourself out and imagine doing it underwater,” he said coolly. It took me the better part of five minutes to get myself untangled from the mono, and, as expected, I was back to the orange gloves and bowling-pin detail.

Luckily, I haven’t had any more close calls when it comes to getting pulled over by a marlin. And after that day, I vowed to make every move a smart one—to really listen and pay attention to every word my mentors were saying to me—and to respect these magnificent creatures. Because I now know that if I don’t, in a split second, things can go horribly wrong, and these fish can severely injure, or worse, kill me.

Since then, I’ve been lucky enough to fish around the globe with some of the best wiremen in the game: Oskie Rice, Marty Bates, Mike Latham, Chris Zaskey and Cory Gillespie, to name a few. And if there’s anything I’ve learned from that fateful day on the North Drop, it’s that without proper technique, it’s only a matter of time until a perfect storm of events lines up to create a really bad situation—one that in no way, shape or form is worth the oohs and aahs from the cockpit crowd. And even though wiring marlin is the be-all and end-all of big-game fishing, it’s not as simple as just grabbing a leader.

Watch: Learn to rig a swimming Spanish mackerel here.

Fish Movement and Performance Know-How

Technique is crucial when it comes to wiring marlin, with most of the good ones learning from mentors of their own. Australia’s Bo Jenyns is perhaps one of today’s best, but he started where we all did: learning to do every single job in the cockpit before stepping up to the transom and grabbing the wire. “I had to earn it,” Jenyns says, “which is something today’s young crewmen should take note of.”

Noticing certain details during the fight can help you in the long run, and there are certain rules most all wiremen follow. Things like hook placement, fish behavior, which wrap to use and the number of wraps to take—all facets of situational awareness—as well as drag settings are important. “I try to see where the hook is and always ask the angler to back the drag off after I grab the leader,” Jenyns says. “This way, the angler won’t get snatched forward in the chair or stand-up harness if I have to let go.” Jenyns also believes that your behavior on the wire should match the fish’s. “If he is coming in nice and easy, I will do the same thing on the leader—pull it up nice and gentle”; conversely, “if the fish is pulling hard and jumping away from the boat, I’ll try to rip its head off,” he jokes.

Jenyns says that any sudden changes in pressure on a well-behaved fish will cause it to react and take off, where a gentle here, fishy-fishy could have easily gotten the job done with a smooth fight and quick release. Knee-jerk reactions to the same fish will cause the fight to continue—wasting precious fishing time, or worse, causing them to flip over, which is never an ideal scenario.

“Small, green fish are very agile and quick off the mark,” Jenyns says. “It’s very easy to pull on them just a little too hard and flip them over, and the next jump will be straight at the boat—maybe even in the boat—so it’s best that you are always ready to let go.”

Greg Hopkins, a well-traveled charter captain who fishes aboard the Kona, Hawaii-based charter boat Nasty Habit, agrees that by suddenly changing pressure on a green fish will cause it to respond in a similar way. “Some smaller fish can be manhandled, but they can, and do, jump in the boat.” He suggests that you size up the fish before going straight in. “Sometimes the way they act will let you know how they are hooked, and then you can wire them accordingly.” Note taken.

Andrew Kennedy—a veteran wireman, light-tackle expert and Marlin University instructor—first earned his stripes on the charter docks in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and grew up watching countless hours of video footage of some of the greats such as Charles Perry. He’s traveled the world as a freelance fisherman, from Central America to Hawaii and beyond, learning from some of the best—including Tiny Walcott, Kevin Roland and Zak Conde—and echoes many of Jenyns’ feelings when it comes to dealing with green fish, big or small.

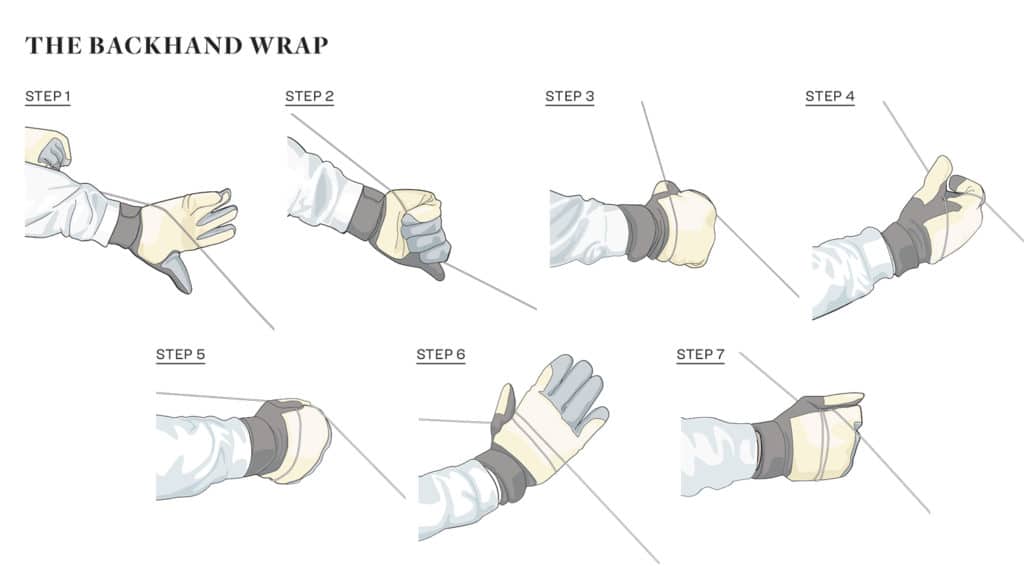

The pinch-pull technique—especially when used with light tackle—is something that lends itself to finesse. Finesse will always win over brute strength, so knowing when to pinch-pull is key. Kennedy will use the pinch-pull method to size up his fish, and it’s what he uses when he first touches the leader. “I like to apply good pressure by pulling down on the leader before taking my first wrap,” Kennedy says, “especially if I want the fish to jump. This way, I’m not flipping it over.” He continues by advising that in extreme pressure situations, he prefers to start with a backhand wrap, which is easier to accomplish when using heavy drag.

It’s probably safe to say that marlin that jump into the cockpit do it because of poor technique—flipping the fish in midair toward the boat. I get it; it looks cool watching a marlin 10 feet out of the air doing flips as the crowd goes wild, and I am guilty of doing it myself, but it can be very dangerous. I like my first touch to be with my strong hand: Pinch, then pull up. Never go right into grabbing the leader aggressively or taking two wraps right away on any size leader. If you take your time, pinch-pulling will get you tight and able to anticipate what the fish’s next move might be, and then yours will be a more educated one.

As a general rule of thumb, never take more than two wraps. Hopkins says he will use single wraps whenever the fish is coming in fast and not pulling against him, especially if the fish is moving in the same direction as the boat. “If I can keep a steady gain, I’ll use only one wrap. If it starts to slip, I’ll take another—like if the fish is digging or pulling back with a lot of force.” And Kennedy agrees by saying that one wrap will slip or cinch, and probably get you hurt.

Read Next: Leave nothing to chance with these bulletproof lure rigging techniques from Hawaii’s Capt. Bryan Toney.

Jenyns agrees that one wrap will slip eventually, but taking three wraps is too many, so he usually takes a backhand wrap first, then reacts to the fish. According to him, the backhand wrap is a wireman’s best friend when dealing with a really tough fish that’s digging on the leader. It’s the only way to lift it up, adding that you use a lot less energy with a backhand wrap than you do with an overhand one. “Sometimes when you’ve been pulling on a big fish on heavy leader for a while and you want to conserve your energy, trying to take overhand wraps will wear you out. The last thing you want to happen is for you to go hard at the beginning, only to have your arms turn to jelly and the captain yelling at you for not being able to pull the fish up.”

Hopkins only ever uses backhand wraps, saying he can gain some leader when dealing with a fish that is bigger and stronger than him. “With the leverage of a backhand wrap, I can sometimes gain another full wrap just by pulling the leader down to me.”

I always want to lead the fish’s bill toward the boat because I have a lot more control that way. If the fish is facing the other direction, then it has the advantage. I’ll take a backhand wrap to gain some line quickly, and take two solid wraps with my other hand. When taking your wraps, make sure you’re taking them between your hips and your stomach. Wiring your fish above your shoulders or bent over the covering board will leave you in the most vulnerable position to go swimming.

Before taking any double wraps, try to predict where the fish is going to go. If it’s swimming—or jumping—away from the boat, don’t be shy to let go or dump your front hand and lunge with your back hand to give the fish a few feet of slack so it won’t flip in the direction of the boat. Picture yourself punching the marlin as it jumps to push it away from the boat.

For example, if you get the leader in the left corner of the cockpit and the fish starts jumping to the right corner, try to stay in front of it as much as you can by sidestepping and beating it to the other side, pinch-pulling the slack over your shoulder. This is a good way to gain some line with little effort. Once you meet the fish on the right corner, lock your knees under the covering board, then go into your double wraps and get tight. If it continues jumping toward the bow, use the rigger as a vantage point to let go of the leader and give the captain time to turn the boat. If the fish is jumping under the outrigger toward the bow and you’re holding onto the leader, you will lead the fish into the side of the boat, causing damage to the boat and possibly compromising the integrity of the line.

“I prefer to be in the corner when grabbing the leader,” Kennedy says. “That way, the captain can fully see what the fish is doing, making it easier for him to drive on it.” Wiring fish from the middle of the transom not only puts the boat at risk for damage, but it also causes the captain to lose track of its movements and increases the chance of running over the fish.

Communication and Using Wind-On Leaders

“When competing at a professional level, communication must be a constant,” Kennedy says, especially when the stakes are high and the lollygag factor is low. “I believe that a daily rundown of what is expected of every team member is crucial so everyone understands what is, or could be, expected of them throughout the day.”

Communication between the wireman, angler and captain is very important, even before anyone grabs the leader. “Communication should be used but not abused,” Hopkins says. “Clarity is important, especially when we are getting the fish close to the boat for the first time, because it’s not always just muscle and will; it sometimes requires a delicate balance of words between all parties involved.”

“If I’m fishing with a new captain, I like to go over many different scenarios with him and tell him where to try to put the fish for me to grab the leader,” Jenyns says. “The captain has to have your back,” he continues, “to be sure he doesn’t put you in a dangerous situation; and all this needs to be thoroughly discussed before the lines go in the water.”

Sometimes I will point to where the fish is going so the captain has no doubt, and on the ride out to the fishing grounds, I’ll sit the angler in the chair and get him perfectly adjusted to the bucket harness, because having an angler comfortable from the get-go will have him focused on his job during a fight, not on how uncomfortable he is.

The wireman also should be constantly letting the angler know when a drag adjustment is necessary and when to reel up slack or when not to. Anglers who are not experienced tend to lose focus toward the end of the fight, which is, at times, when they should be focused most. This is especially true when using wind-on leaders.

Personally, I like 30-foot leaders, and most professionals do as well, but there’s a time and place for both. If the crew is short a second mate, or if I’m fishing a kill tournament, I prefer to use wind-ons, and I always make my own. That way, if something fails, I alone take the blame.

While using wind-on leaders might be the safer route when fishing heavier tackle (and it is when everyone is on the same page), you’re only as strong as your weakest link, and this will hold true if the angler isn’t paying attention. On a few occasions, I’ve had the angler reel my hand right to the rod tip, leaving me completely defenseless.

Jenyns says he doesn’t trust that the angler won’t wind him up with the wind-on. “There’s nothing worse than when you’re pulling on a fish, and all of a sudden, your angler tries to wind, and stretches you between him and the fish. This can put you in a very dangerous situation very quickly.” Stretching out the wireman while he has two wraps on both hands makes his ability to get out of those wraps nearly impossible, and this is where the beginning of the proverbial perfect storm is about to happen.

In my 16 years of fishing as a full-time mate, I’ve noticed that some people are just born to marlin fish. They might do the same thing as every other mate, but they do it better. I was taught by some of the industry’s best, but I am definitely not one of those people. Some things came easier for me than others, but it was mostly trial and error that taught me what will work and won’t, no matter how hard I try to make it.

There is a quote I’ve heard throughout my career, and it still rings true today: It’s not one thing that makes a good fisherman; it’s a bunch of little things—executed at just the right moment—that allow you to capitalize on an opportunity to the best of your ability.