Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

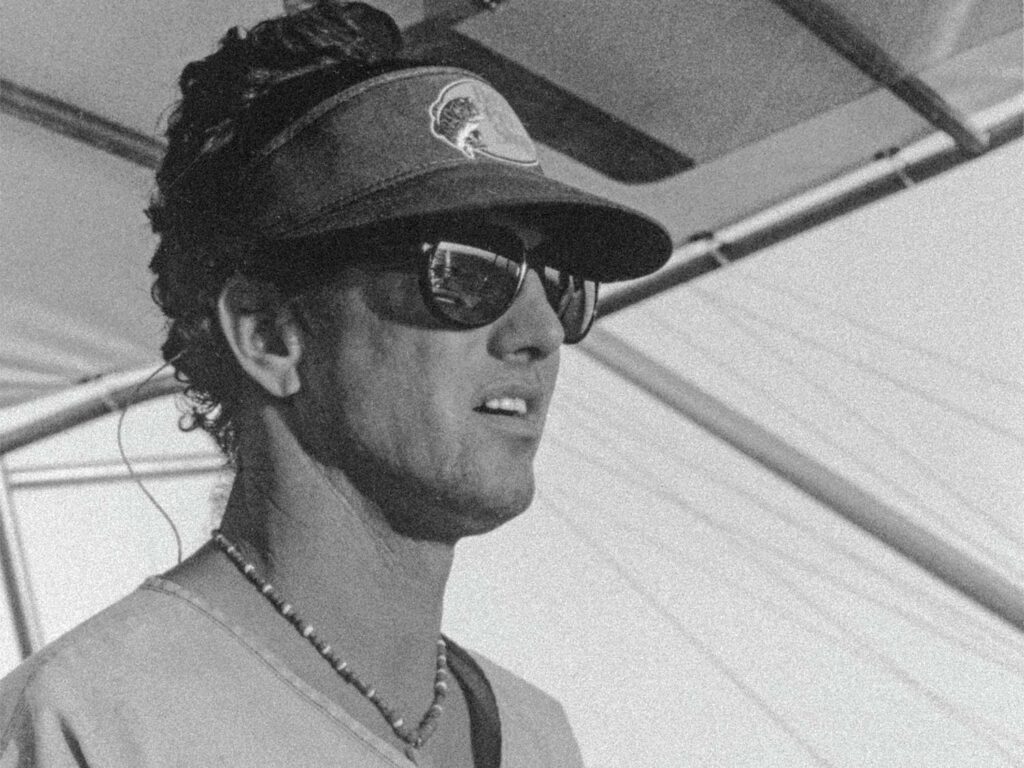

What is greatness and how do you measure it? Is it hard work, dedication, innovation, drive, being a student of the game, trying experimental things, or having commitment? Or maybe it’s creating an environment for teamwork, being innately inquisitive, using data collection to make assumptions that can be proved or disproved, or questioning the status quo? In Capt. Peter B. Wright’s world, all of these were true.

Few of us get to experience true greatness in the line of work or hobby we choose. Those of us who have had the good fortune to work, fish, travel, argue, socialize, or just be around Wright have been exposed to his personal greatness, in all its perfect and imperfect human form, only limited by his time on Earth. Wright passed away on January 23, 2023, at the age of 79, after a long and difficult battle with Alzheimer’s disease.

Australia and Those Giant Black Marlin

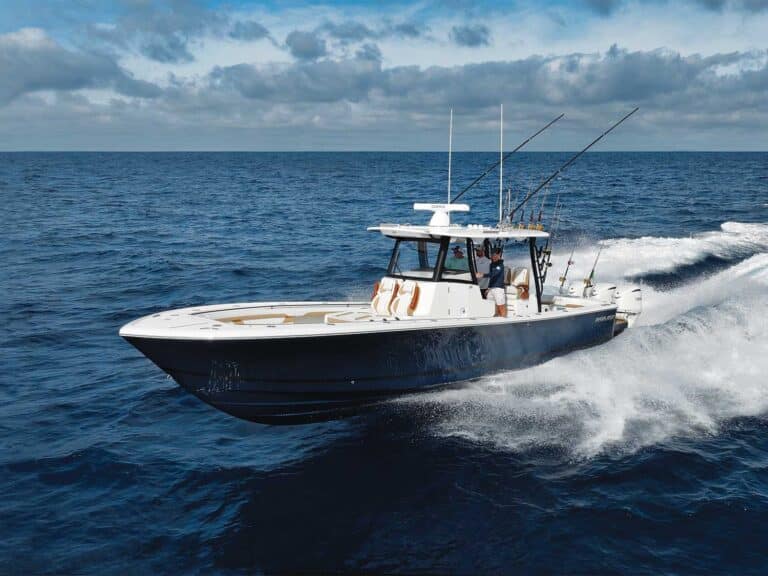

When it comes to the best of the best in any arena, in their time and place, everything comes together to create an opportunity for incredible success. In Wright’s case, it was the fledgling black marlin fishery at Cairns, Australia, that brought together a collision of his skills, inquisitiveness, love of fishing, and sense of adventure that created the mind-boggling career he amassed there.

To be sure, no one did more to promote the Cairns fishery to anglers in the US with his stories and photographs. He created an opportunity for an industry by mixing his skillset with a business acumen and his ability to entertain guests in a safe and big-fun way.

Capt. Peter Bristow, who ran Avalon for the heavy-tackle season there for more than 25 years, came to Cairns a year after Wright, and they became quick friends. Bristow says: “Peter was the most prolific promoter of Cairns who ever set foot on the dock, who ever existed. I mean, George [Bransford] set the place on fire catching that first world-record grander. Peter was his crewman after that. The place where it all came from was that heavy-tackle group in Bimini and Cat Cay [in the Bahamas], and fortunately for us, we had the honor of the anglers coming down who brought their captains and crews with them. Peter really put it on the map with all the people he brought down. He was the strongest promoter we’ve ever had.”

A Tireless Drive for Success

All this talk of greatness would lead one to believe that the person was near-holy, a spiritual icon able to walk on water. Wright was fully human. He made mistakes, and freely admitted it when he did. He’d sometimes cut his schedule too close, so he didn’t have enough time to properly prepare. He relied on his deckhands to make up for it. He could argue with a tree if he had a point to get across, which made many folks bristle at his stubbornness or conviction in his position.

The scientist in him collected data points all the time, and he used that data to make his points. And you’d better not try to argue with him without a large proven data sample of your own. If you speculated or fiddled with the facts, he’d nail you.

Wright had great compassion for family and friends. He’d go out of his way to help with something if he could. He was patriotic and proud of his birth country, and his adopted one—Australia.

Wright used his acute understanding of the mechanics of his job with ease, mastering the logistics of supplies, provisions, tackle and crew for those long seasons on the reef. When you fished and traveled with Wright, he would make sure that the guests had a full day. He’d introduce them to diving, fishing, throwing poppers, vertical jigging, shooting flying fish off the bow with a shotgun—whatever that place offered—while he squeezed all the benefit out of it to give you a complete and robust experience. There was no sitting at the dock; there was always an adventure awaiting.

Innovation and Creativity

Another icon from the Cairns fishery, Capt. Dennis “Brazakka” Wallace started fishing there the same year Wright did. The two had endless adventures together throughout their lives, and saw the development of so many things with tackle and gear that are regarded as commonplace today.

“In the early days [in the 1970s], we were having a lot of trouble with wire,” Wallace says. “We were using 0.040 piano wire, and that was good strong wire, but not for these marlin bouncing all over the back of the boat. Pete was the one who instigated like he always did and got us all together, saying, ‘We’ve got to do something about this.’ So, we started double-wrapping it, and that’s where the double-wrapped leaders came from. Then we went to stainless, and Pete’s behind it all the way.

“We were straightening flying gaffs at the back of the boat,” Wallace continues. “Of course, the fact that the fish were pretty green didn’t have much to do with it,” he says with a grin. “But we are sticking them with gaffs, and they were straightening out—all the best gaffs you could possibly buy. So, we went to Earl Elders, an early guy who was building the towers and the stainless-steel bow rails and things. One day, it was really blowing, so we went around there with Pat Gay, who later caught a world record on 30-pound-test with Peter, 800-plus pounds back in 1971.

“Pat’s an engineer by trade from Brisbane, and he came up with the back-banded gaff. He said that if we reinforced it, it can’t straighten because one band is fighting against the other. So we made one, hooked it to a tree, and tried to straighten it out with Peter’s 4×4. We couldn’t—we pulled the bloody tree down instead. So, Pete was the instigator of all that sort of stuff, and if it wasn’t working, he’d say, ‘Let’s go do this’ and ‘Let’s go do that.’ It would be him and me and Bristow, and we’d be going for all these new things. At the time, we didn’t realize that we were pioneering and that Pete was instigating the whole time. Another time, we were having trouble with the Dacron line breaking—the waxed stuff. It never used to break before, but what we found was that when the line was running out as you were fighting a big fish, it would hit the top of the back guide, the very first guide on the rod. So we went to the manufacturers at Fin Nor, and we had them put a roller on the back top of the very first guide, so if the line hit that, it couldn’t chafe.

“Then [IGFA President] E.K. Harry came down one year and said: ‘Jeez, you guys are killing some pigs out here. We’ve come out to have a fish.’ He was at Lizard Island, and that’s when we had a meeting with him, and he said, ‘We’re thinking of knocking the doubles back from 30 feet to 15 feet.’ We said, ‘This is not going to be any good,’ but when they did it, we improvised, adapted and overcame. That’s how Peter worked.” A few years later, the IGFA relented and changed the rules to the current format.

Wright went on to set numerous IGFA world records with his anglers. He was also responsible for landing a 1,442-pound black marlin that remains the largest ever weighed in Australia, as well as the women’s 80-pound record of 1,323 pounds, a record that is still standing after 46 years.

The wind-on leader was another of Wright’s many innovations. In the early 1970s, his brother Philip came down to be his mate and broke his wrist. Bristow says: “Pete and I were sitting there, and he’s trying to figure out what the hell he can do with Philip if he can’t wire a fish with a broken wrist. Pete asked, ‘What do you think about having no leader and just winding the swivel on?’ and I asked, ‘Well, how are you going to join it?’ We went back to the house and rang Elwood Harry, the president of the IGFA at the time, and asked him about it. Harry said, ‘They do it in fly-fishing all the time,’ so then we looked at knots, but it didn’t stack up. It was Pete’s idea to use a splice so that the connection would pass through the guides, and after that, the rest of the world started doing it that way. But it was his idea, which was born out of necessity.”

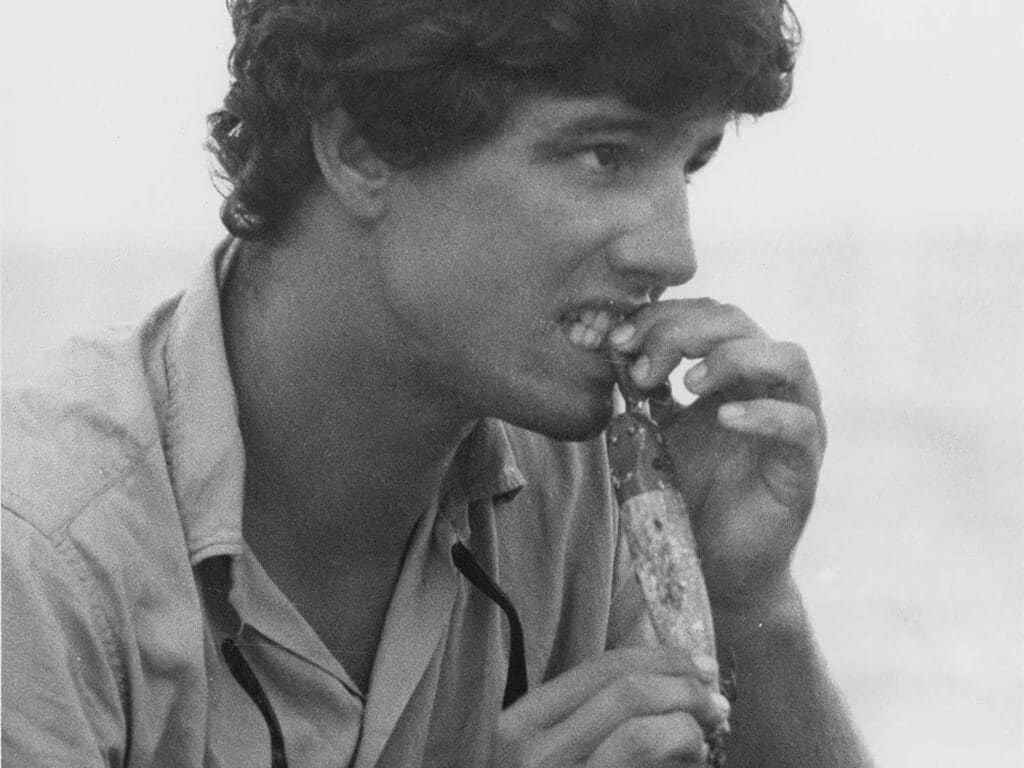

Hawaii and the Softhead

Longtime friend and industry promoter Rick Gaffney fished with Wright a bunch in Hawaii. “I first met Peter in the 1970s when he partnered with Capt. Jeff Fay to introduce the 37-foot Rybovich Humdinger to the Kona blue marlin fishery,“ Gaffney says. “One moment that I still vividly recall began as I watched this yellow Rybovich approaching from the north as I idled south in 100 fathoms along the Red Hill ledge, slow-trolling a live aku. A sudden movement at the top of the Rybovich’s tower caught my eye, and I watched in disbelief as Peter descended like a firefighter down a pole. He’d seen the approach of a big blue marlin, flew down a tower leg, and hit the cockpit poised for action.

“Peter did everything fast in those days,” Gaffney continues. “He talked fast—the Aussies dubbed him the ‘Lauderdale Lip’—he acted immediately on any opportunity, like his partnership in the Rybovich, and when he was fishing, he moved with an alacrity that was rarely witnessed in the laid-back fishery of Kona.

“On that memorable day, the big marlin propelled itself upward in slow motion, but something odd was draped over its iridescent silver-blue head. This reddish-brown, tassel-like rubbery material obscured part of the fish, and Peter was laughing hysterically.”

Draped over the now-furious blue marlin were the remains of Wright’s prototype softhead lure. He had tightly rolled a bundle of the red inner-tube rubber, the preferred inner skirt material for Kona’s famous trolling lures. He had pierced the bundle for the leader, then rigged the resulting snub-nosed skirted assembly with hooks and run his experiment back into Humdinger’s easy wake. The bundle popped and smoked enticingly, and it produced the desired result, but the assembly failed in the slashing attack and explosive first jump of the fish, unrolling the fringe-like material and causing it to flail and flop around, turning a successful fishing trial into a comedy.

“They caught the fish,” Gaffney says, “and Peter’s soft-lure concept was now proven. And yes, the ‘Mouth from the South’ regaled us with every detail of his theory on why soft lures were more like real food than the molded hard-resin lures proven by Kona’s earlier icons. Peter merely needed to find a rubber-molding genius to turn his concept into a product. Frank Johnson at Mold Craft proved to be the right man for the job, and the rest is history.”

The Move to Marlin

As I transitioned from charter-boat captain to peripatetic fishing journalist, my career blossomed in part thanks to Wright’s generosity. He introduced me to both the giant black marlin of the Great Barrier Reef and giant bluefin tuna in Bimini, and to many of his peers. Wright was always willing to find a spare bunk for me so that I could observe, photograph and document his preferred fisheries.

We became close, and many years later at a boat show, in a late-night moment that may have involved more than a little rum, I asked him a question that uncharacteristically caught him off guard: “What are you planning to do when you get too old to fish?” The seemingly ageless Peter Pan of big-game fishing was flummoxed by the concept but replied, “Like what?”

Knowing he was a world-class storyteller, I suggested writing, teaching, and appearances at fishing, boating, and outdoor shows. He initially proclaimed disinterest but soon took me up on an invitation to join me at an outdoor expo I was working in California, where he seemed to have an “aha!” moment. Soon after, Wright had pretty much replaced me on the pages of Marlin, and he became active on the show circuit, sharing his skills, expertise and stories with hundreds of thousands of fishermen.

Wright’s contributions to our industry are extensive, but perhaps his greatest legacy is manifested in the many mates and budding skippers he mentored into world-class captains—such as Laurie Wright, Kevin Nakamaru and Jason Holtz, among many others—skippers who build on his legacy wherever they fish.

It would take a book to share enough stories to provide a full measure of the man, but as I think of Wright today, I recall being awestruck by his flawless delivery of “The Man from Snowy River,” Banjo Paterson’s epic poem about hard Australian stockmen and the horses they race:

And where around The Overflow the reed beds sweep and sway

To the breezes, and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word today,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

And so it is, in the wake of his untimely passing, that we fishermen share stories of his long and memorable ride.

The Legacy We Leave

Capt. Bark Garnsey has spent a lifetime with Wright, starting their fishing careers on the opposite sides of Hillsboro Inlet Bridge. “In those days, the bridge was opened and closed by hand,” Garnsey says. “Pete was on the inside, working for Capt. John Whitmer at the tender age of 13 or 14. I was on the outside, working for my father on the Helen S drift boats, and was about three years younger than he was.

“When he started writing for the various magazines, he never failed to entertain his readers and quite often managed to irritate them at the same time,” Garnsey continues. “Peter was never shy about engaging in a good argument if you didn’t share the same point of view. On more than one occasion, if you didn’t disagree with Peter, he would be happy to take up the other side just to have something to argue about! As all fishermen know, there is a fair amount of spare time when fishing, but rest assured, that was never the case when Peter was on board.

“Peter would often join me and my crew and Stewart Campbell on our trips, often to write a magazine article, but mostly he just loved to fish, and we loved having him along. Stewart and Peter would always find something to bet on and argue about.

“Charles Perry asked me recently about the places that Peter fished with us. The most memorable were our times in Madeira, the Canary Islands, Cape Verde and the Ivory Coast. I had the privilege of fishing with Peter in Australia. I don’t have the time to list all the things I learned from Peter Wright through the years, and even if I did, I probably wouldn’t share them anyway. He was a great fisherman and boatman, but most importantly, he was one of the best friends I’ve ever had. He will be missed.”

The influence Wright has had on the sport-fishing industry is irreplaceable and nearly impossible to measure. We’re all in a good place having been brought along by him—of that there is no doubt.

The last few years were cruel to such a kind and thoughtful man. That most horrible of diseases, Alzheimer’s, wreaked havoc on him, ever so slowly eroding the brilliance, quick wit, wry humor, and scientific analytics that made him so valuable to so many. During our visits, it was hard to witness, but he fought it with the dogged diligence that served his career so well. With his loving wife, Erin, by his side, providing a care unrivaled in any institution, they turned to science for an experimental treatment that proved effective for a time.

For me personally, Wright was the most cerebral fisherman I had ever been around. I often commented that I learned more through osmosis, just hanging around him and listening. He introduced me to some of the best deckhands I’ve had the honor to work with over the years, who have become great friends as well. He was a hardworking business partner in our various enterprises, and the finest kind of friend you could have.

Read Next: One of Wright’s favorite destinations—Australia’s renowned Great Barrier Reef.

We had so many adventures together working on projects, fishing, consulting, traveling, shooting, and doing trade and countless boat shows together. There were many layers to Wright. While tied up next to the mothership one evening, sitting at the dinette table of his boat, Duyfken, I remember looking around at everyone’s faces absolutely amused listening to him recite Rudyard Kipling word for word, which is no easy task. He was holding court, and he loved an audience.

It’s been a typhoon of memories flooding back putting all this together. As so many of us from around the world have connected to talk about Wright, the laughs and smiles have been abundant. As I said to one of our shared deckhands, Nigel “Basher” Semaine, when the urge strikes to have a rum at the end of the day, I can’t help but hear Wright’s trademark laugh as he’s squeezing the lime and offering a hearty, “Cheers, mate!”

Here’s to you, Peter—thanks for everything.