Each spring, the pristine grounds along the northern Great Barrier Reef experience one of the world’s greatest natural wonders. The nutrient-rich Coral Sea currents trigger all kinds of resident and pelagic species to gather and spawn in this part of the world, and it is here where we can witness some truly astonishing sights. Thousands of giant trevally travel in a spawning aggregation so tightly packed that they appear to be a detached part of the reef, causing some skippers to panic when approaching such a ball of huge fish that they quickly turn away until they’ve worked out what they’re actually seeing. Giant 1,000-plus-pound female black marlin tail down-sea in the company of several smaller males in their own spawning dance. During the 2018 season, one vessel caught 144 black marlin in just two months—ranging from 200 to 1,250 pounds—making this, undoubtedly, the most prolific black marlin fishery in the world.

When It All Started

Many anglers still ask, “How was this incredible fishery discovered?” It’s an interesting question, because before the early 1960s, no one really knew about it—few local fishermen ever ventured out past the edge of the Great Barrier Reef. They fished mostly the inside grounds, which are made up of scattered reefs and coral heads where juvenile black marlin, sailfish, and all kinds of mackerel and bottom species were abundant. It wasn’t until two marine biologists, studying the Japanese longline statistics in the Pacific, brought to light the staggering catch rates of large black marlin in the Coral Sea.

Their papers and maps, entitled The Distribution and Relative Abundance of Billfish in the Pacific, were released in 1965 by US Institute of Marine Science in Miami scientist John Howard, along with Dr. Shoji Ueyanagi from the Nanki Regional Fishery Research Institute in Japan. Their information showed that the catch rates and size ranges of black marlin caught were astonishing. Along with marlin, huge numbers of massive yellowfin and bigeye tuna were also being landed. This scientific report naturally had fishermen along the eastern coast of Australia gasping in disbelief.

Watch: Tempt a black marlin with this swimming mackerel.

Bransford’s Grander

An American captain named George Bransford had been stationed in Cairns during World War II and had spent his recreational time talking to the local fishermen, who told him there was an abundance of black marlin in these waters. Bransford’s love of the Great Barrier Reef saw him move back to Cairns from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in the early 1960s, where he had been running a charter boat. His first job was to build a gameboat. He soon met Alan Collis, a local fisherman and boatbuilder. In 1964, they launched the 32-foot Sea Baby. In 1965, when Bransford heard about the Japanese longline reports, it only confirmed his earlier thoughts that there had to be spawning grounds somewhere along the reef. And as the capture graphs and maps accompanying these scientific papers confirmed, the outer reef was alive with black marlin. Giant ones.

Bransford’s first venture offshore was in September 1965, and he had no trouble catching all kinds of small tunas and mackerels for bait. Sea Baby caught two black marlin around the 250-pound mark, and also saw a couple of much larger fish. That day, around 2:00 p.m., one of their baits disappeared down the throat of a real monster, and fishing only 80-pound-test tackle, the battle was quite one-sided, to say the least. The huge marlin simply dominated the fight and couldn’t be chased down. The fight took them well out to sea, and Bransford estimated that they were 30 miles off the reef when the line finally parted after eight hours. In the pitch-black darkness, they were lucky to see the navigation light on Euston Reef to guide them back to the edge.

After a few more unsuccessful trips that year, the sight of the giant marlin made Bransford only more determined than ever to catch one. With a few modifications to the boat—including a better fighting chair—they ventured back out to try again.

On September 26, 1966, with new deckhand Richard Obach aboard, they hooked up with a large marlin that Bransford thought was much smaller than the beast they had struggled with the year before. After a two-hour fight, the marlin was finally gaffed and secured alongside. When they tried to get it into the boat, they had trouble lifting its head out of the water. They had to tow the marlin all the way back to Cairns, where it later weighed an astonishing 1,064 pounds. On 80-pound tackle, the fish was a new IGFA world record.

Notorious Cairns

It didn’t take long for the sport-fishing world to find out about this record-breaking black marlin, and a couple of Aussie anglers were quick to get to Cairns the following year. Arthur Stewart absolutely annihilated the Australian 130-pound-test record with a 1,156-pound black marlin, a record that was short-lived when another Aussie, Basil Mitchell, weighed a 1,208-pounder. Suddenly, the little sugar-cane town of Cairns was on the world’s big-game-fishing stage. And even with a few vessels organized to come up from the southern states, there simply were not enough capable boats to cater to the influx of interested anglers from around the world.

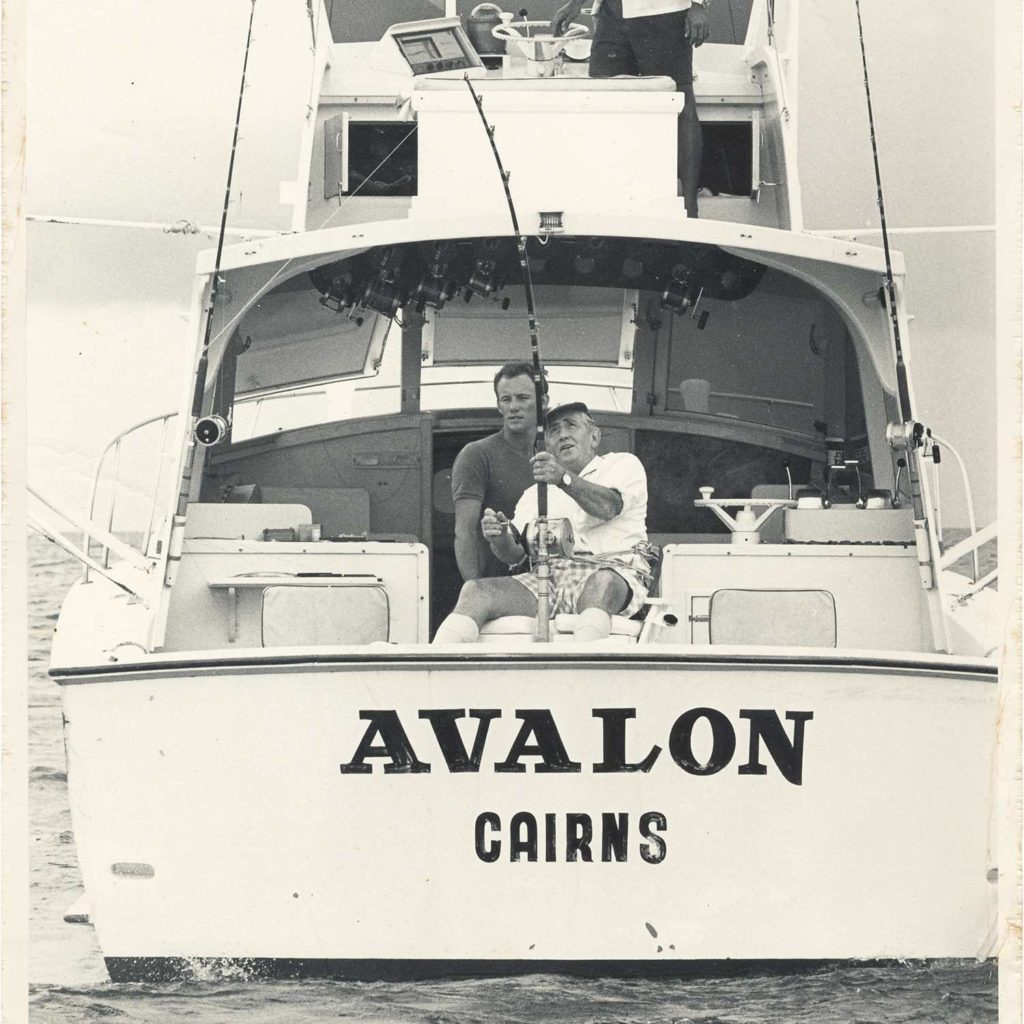

A number of vessels were now under construction in Cairns, and in the late 1960s, Sydney’s Caughlan family ordered the first 40-foot Woodnutt gameboat to be built. It was called Kanahoee and was skippered by Alan Collis, who didn’t take long to christen it with a grander of his own. At the same time, another vessel was built by none other than Capt. Peter Bristow. The mighty Avalon went on to be a real marlin machine, and one of Bristow’s heavy-tackle anglers was the highly skilled JoJo Del Guercio, who weighed 18 granders in just six seasons on the reef.

Heavy-tackle records fell like dominoes, and the 80-pound record that started it all was beaten by Bill Wilkie with a 1,077-pounder. This was broken again the following season by Sydney television personality Bob Dyer with a 1,138-pounder. Dyer’s record was quickly knocked off by Mead Johnson, former vice president of the IGFA, with a 1,218-pounder. Eventually, in 1976, Buster May landed a 1,347-pounder—a record that still stands today.

The 130-pound record changed dramatically as well when New Zealand’s Sir William Stevenson weighed a huge black, only to have it knocked off by Guercio with 1,281-pounder. Both were taken on Bristow’s Avalon. By 1973, more records tumbled before the first black marlin over 1,400 pounds was captured by Garrick Agnew, his being a 1,417-pounder, which was then toppled by Michael Magrath’s 1,442-pound beast.

Tackle in Question

Most of the heavy tackle in those early days was inadequate, even with 130-pound-test line. Notably, the old star-drag reels just couldn’t apply enough pressure needed to raise a giant black from the depths. When Penn introduced the 130 International, and later, its two-speed model, many captains switched over to them for their improved strength and reliability. The man who cut his teeth on those early Penns and fine-tuned the drags to perform even better than off-the-shelf versions was none other than the tackle master himself, Jack Erskine. He was also a fine rod builder, and the magnificent 130-pound-class rods Erskine built to handle the giants not only looked nice, but they performed brilliantly as well. Erskine also designed and built a heavy-tackle bucket harness, which many other tackle manufacturers soon copied. Erskine was a perfectionist, whether on the water with a rod in his hand or at his lathe, machining intricate drag plates.

No Light-Tackle Records Were Safe

With such a cross-section of black marlin ranging in size from tiddlers to monsters, it wasn’t long before the Cairns grounds attracted the world’s finest light-tackle anglers. Five who immediately come to mind are Kay Mullholland, Marg Love, Bob Oliver, Peter Mahood and Mike Levitt—all who have held, or still hold, world records for blacks off Cairns. I was at Lizard Island in 1982 when Mullholland weighed her near-grander on 20-pound-test, a fish that weighed 998 pounds and is still the current world record. She also held the 50-pound world record with an 874-pounder from 1976 until Stephanie Osgood blew it away in 2014 with a black weighing 1,111 pounds. Oliver has held the 30-pound record with a 1,079-pounder since 1980, while Mahood has held the 20-pound-test record with a 1,051-pound beast since 1976. I fished with Levitt a few times and was close by in another boat photographing him in action when he broke the 12-pound record in 1981 with a 737-pounder. In 2001, Levitt was back in action when he broke the 16-pound world record with a 631-pound fish. The other interesting Cairns world record that has stood now for 50 years is the 1,124-pounder taken on 50-pound-test by New Zealander Eddie Seay.

Lures vs. Bait

Cairns has traditionally been a natural-bait fishery, but in the mid-1980s, a few vessels started using artificial lures. One captain, Peter Kirkby, ran a number of successful vessels in Cairns and certainly led the charge in the lure department. Kirkby developed his own black Hypalon rubber heads that he machined on a lathe to a shape he liked; some had a scooped-out face, and others a flat face. These softheads smoked like crazy, and he started trolling them at a little slower than normal speed of around 6½ to 7 knots. The giant marlin loved their action, and Kirkby’s success soon had other skippers interested. Kirkby gave away a lot of his lures to his buddies to try; a few captains also started using the Mold Craft softheads. The first grander taken on a lure happened in 1991, when Capt. Laurie Woodbridge on Sea Baby IV nailed a 1,041-pounder on a Mold Craft Wide Range. When Woodbridge retired, his deckhand, Capt. Ross Finlayson, took over the helm, and a giant black took a liking to the Mold Craft Super Chugger he was pulling. Weighing in at 1,257 pounds, it is still the largest black marlin ever taken off Cairns on a lure.

Enter the Circle Hook

In the late 1990s, the Cairns fishery saw another interesting change. Before the start of the 1999 season, Capt. Peter B. Wright strolled down the Cairns dock handing out Mustad circle hooks to the captains and crews—most of whom didn’t want to change their techniques because J hooks had been used since the fishery began. Using circle hooks would mean changing the bait-rigging methods, and hooking the fish was another issue to consider altogether. I’ll never forget what Capt. Dennis “Brazzaka” Wallace said to Wright at the time: “They’re bloody tuna hooks, Peter. What the hell are you thinking?”

After a few seasons, many crews had perfected how to rig their swimbaits with circle hooks by anchoring them a few inches away from the bait’s head and using a lead weight stitched in the belly to keep the bait swimming upright. Rigging the skipbaits required only a few small modifications, and instead of the hook getting stitched tight to the bait’s head, they found that it worked better a few inches away as well. Additionally, many crews found that circle hooks worked much better with heavy monofilament leaders instead of the old reliable 400-pound-test galvanized single-strand wire.

Read Next: Learn to make the best of what you have when it comes to rigging baits.

Getting the circle hooks to set was certainly a learning curve, and some captains became so frustrated that they switched back to J hooks, but most of the fleet persevered. After a few seasons, they had finally sorted out the changes needed to get the circle hooks to work. These days, most everyone is using them and, like many other places, the tournaments in Cairns and Lizard Island have made them mandatory.

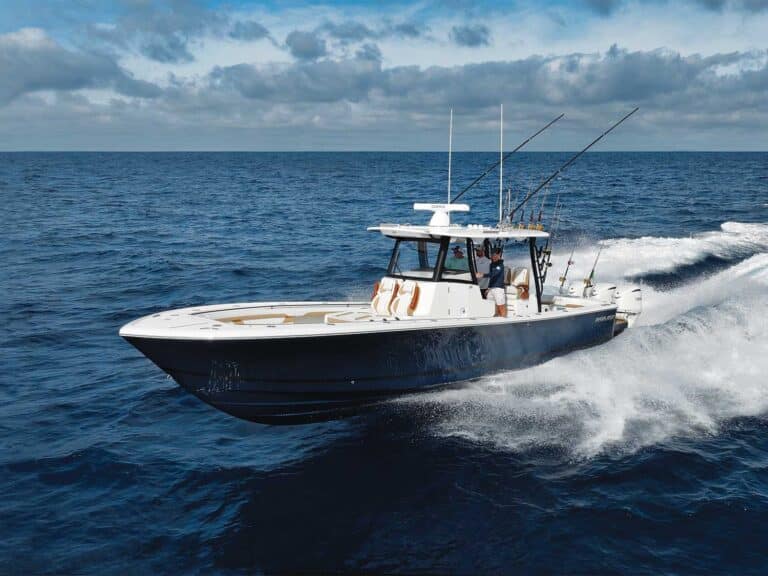

The Modern Fleet

The old dayboats running in and out of Cairns have all but gone, and even the mothership numbers have fallen in recent years. Today, the majority of the modern battlewagons are outfitted for living aboard and offer a comfortable stay out on the reef for a few days or up to a week or so. The little country town of Cooktown—north of Cairns—is where many of the charter boats work from, and the town is set up with a great service for fuel, water and ice, as well as a general store that delivers quality food and drinks down to the dock when needed. The nice part about operating out of Cooktown is that it’s close to Lizard Island and the magnificent Ribbon Reefs. During the majority of the season, the bite happens along these reefs, and they also make for great evening anchorages. Staying along the Ribbons, you’re just minutes away from marlin fishing, plus the area offers superb popper-fishing for giant trevally and bottomfishing for all kinds of tasty species. Some of the best dive sites are here as well, including the always popular Cod Hole off Lizard Island.

While the time frame for reopening Australia for visiting anglers from the United States and Europe remains up in the air right now, the fishing remains just as good as ever off the Great Barrier Reef. It’s the opportunity to catch the black marlin of a lifetime.

The Rich and Famous

In the 1970s and ‘80s, anglers from all over the world lined up to fish for black marlin out of Cairns, including many famous celebrities. Among them were actors Lee Marvin, Wilbur Smith and Ernest Borgnine. Two of the world’s best golfers—Jack Nicklaus and Greg Norman—turned up, and each caught granders on the reef. The president of McDonald’s, Fred Turner, andformer President Jimmy Carter also came to fish. Aussie tycoon Rupert Murdock visited, and rockers Tim and Jon Farriss of the band INXS loved their time on the reef, catching giant black marlin from their own 35-foot Bertram.

This article was originally published in the August/September issue of Marlin.