How does faux teak stack up to real wood? Well, it promises half the cost, near-zero maintenance and minimal downtime. Faux teak is rapidly replacing the real deal for helm pods, toe rails, bulkheads and transoms—and really any traditionally teak-clad surfaces. I asked a few artists, along with some boatbuilders and yard managers, if faux teak is all it’s cut out to be.

“Real wood transoms look great, but it’s hard just to find boards that fit, much less choose the right piece of teak,” says Roy Merritt of Merritt’s Boat & Engine Works in Pompano Beach, Florida. And this is particularly true of larger boats with broad transoms. “Faux gives us the ability to have a beautiful transom without the added upkeep of wood,” he notes.

Merritt’s has shifted from all cold-molded to composite construction over the past three decades, although it still builds both. If cost of ownership was a driving factor, then it seems to be again with brightwork. “Take an 80-footer,” Merritt says. “Just to strip and revarnish a real teak toe rail is so expensive, and when it’s done, it starts out looking great, but over time loses its color. Faux looks good forever.”

Faux History

The seeds of the current trend in faux teak began with boat owners seeking quicker, less expensive repairs. Artist Adair Ward grew up boating in Islamorada and worked aboard motoryachts. When she married a sport-fishing captain, cocktail season in Newport, Rhode Island, conflicted with blue marlin season in the Virgin Islands, so she took up varnishing instead. “I started doing faux teak for temporary repairs—Band-Aids on small dings until [the boat schedule gave us] a chance to strip it all the way down,” she says. “The repairs got larger: bill marks on transoms, water damage on bulkheads.”

Watch: Learn to rig a swimming Spanish mackerel here.

Employing paint to repair woodwork on yachts dates back to at least the late 1980s, when the original Rybovich yard mimicked wood grain to blend transitions where new wood repairs met the existing wood finish. Ward, however, might have been the first to paint faux teak in place of real wood. “Back around 2006, I started with teak step boxes and dock boxes to test durability,” Ward says. Within a year, she was painting teak onto toe rails, helm pods, fighting chairs and entire transoms. “Teak is absolutely beautiful,” she says, “but I wanted to provide that classic look without all the maintenance.”

Wood…or Not

Josh Everett’s parents drew him into both fine woodworking and art. Everett eventually traded a Manhattan commercial-art career for an Outer Banks woodworking job at Bayliss Boatworks, and then he began painting graphics on yacht transoms. “I saw Ward’s work on an 87-foot Spencer, and I thought her faux was really cool,” Everett says. “I put real teak on boats, and that background in carpentry let me emulate the seams and joints accurately and bring that craftsmanship into faux. As a woodworker, I want to be 100 percent convinced that my faux looks like real teak.”

But here’s where faux teak saws against the grain: “Working in faux, you have more flexibility,” Everett explains. “Merritts and Ryboviches used quarter-sawn teak with straight grain and no knots because that’s what held up best in traditional wooden boats. Carolina builders often use a little darker wood with more grain pattern, and as an artist, I can offer light, medium or dark wood tones. It can be straight-grained and even, or wildly figured.”

“The beauty of faux is that I put the grain wherever I want,” says Lou DeFusco, an artist college-trained in paint and sculpture. DeFusco swapped residential faux-finish success for a job in the cockpit of an 80-foot Merritt, and then ran his own charters in Costa Rica and Rhode Island. When he’s not fishing, he is painting yachts with faux. “You can analyze my transoms like a painting. I use areas of interest and areas of calm along with color variations in the composition to complement one another. The name and graphics play off that too, to lead your eye around the transom.”

With his residential faux background, DeFusco works in far more than just faux teak. Faux stone saves weight; faux-wood paneling takes to curved surfaces; antiqued or distressed wood, metal, carbon fiber, and animal hide are all readily re-created with paint, typically for less money, with lower maintenance, and in durable high gloss.

Maintenance Comparison

Faux isn’t, however, without its detractors. Michael Rybovich incorporates cutting-edge boatbuilding technology in his yachts, but all his boats include once-living wood at their core. “Faux teak was invented by Satan,” Rybovich says, “along with simulated wood-grain vinyl, synthesized music, and blowup dolls,” he says, not entirely tongue-in-cheek. “It reflects the cheapening of modern life. Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, who were real singers making real music, told us a long time ago: “Ain’t nothing like the real thing, baby.” If a customer doesn’t want to deal with brightwork, that’s fine; we’ve painted out a lot of boats for practical reasons, but ‘fake’ is not synonymous with practical.”

Rybovich disputes the maintenance savings of faux too. With quick touch-ups of minor dings to protect the wood, varnish with urethane and topped with clearcoat often needs only a maintenance coat every two years, and it should last five to eight years before stripping it back to bare wood. Faux-teak transoms, on the other hand, benefit from fresh UV-protective clearcoat every three to five years, and can easily last a decade.

“When you get a bill mark through a fauxed transom, you can usually buff it out,” Ward says. Faux is also touched up with paint instead of varnish. “Varnished teak gets lighter with UV exposure, so new touch-ups are darker than what’s around it; it starts to look like bullet holes in the transom. The only way to get it back to one uniform color is to strip it.”

Cost and Convenience

Even allowing for similar maintenance periods, the numbers favor faux. One of Ward’s clients fishes hard, and every few years, she completely redoes the faux transom—in about one week and for well under $10,000. To strip and revarnish the same-size authentic teak transom would approach $15,000, and take close to three weeks.

Time and cost comparisons hold true on initial installation as well. “We lay down multiple clearcoats in one spray application, then sand it, put down two more coats of clear, and buff it,” says Chuck Kelley, general manager of Bristol Marine in Somerset, Massachusetts. Including the artist’s time, faux-wood transoms and toe rails can be done in a week. “To do that in varnish takes a lot of coats, with sanding between each coat, just to fill the wood grain—you’re looking at many weeks in the yard.” Bristol Marine recently installed a real-wood transom overlay as well as a similar faux-teak transom, with real wood costing more than double the faux.

Read Next: Maintain your teak deck correctly with these techniques.

“We’d do just a handful of toe rails and transoms in real teak, maybe two or three of each in a year, if that,” says Keith Monahan, Viking Yacht’s sales manager. “Now with the option of faux, we’re doing 15 or so every year.” For builders like Viking, though, faux actually takes longer. “Any paintwork—be it hull paint or faux teak—has to be done after the boat leaves the production line, requiring additional time,” he adds. “Real teak can be completed before the boat leaves the line.”

Choosing an Artist

The artists I interviewed warned against cheap imitators brought out by the current popularity of faux. “People in the sport-fishing world see a lot of boats,” Everett says. “Look at examples—really look at them—and see what those artists are providing, then seek out the one you like.” He also warns to choose a yard based on painting expertise, because the final clearcoat affects the look and longevity of the faux finish.

“Some artists paint only one way, so that is what you get,” DeFusco says. “Others will work with the owner. Walk the docks and take photos of transoms you like—real wood or faux—and have an artist create a few samples.”

“Getting out what the owner really wants—that can be the toughest part of the job,” Ward adds, but choosing an artist isn’t as easy as picking a color and a grain pattern. “Look for consistency. Some artists are great on one job but not on another,” she warns. “Check with previous clients: Did they show up on time? Were they done on time and for the contracted price?”

When cutting to the core, the choice between real wood and faux wood is purely personal—you pay a little more for the ineffable satisfaction of real wood, or appreciate the beauty of teak with lower maintenance and less downtime with faux. Overanalyzing beyond that really is missing the forest for the trees.

Step Outside the Box

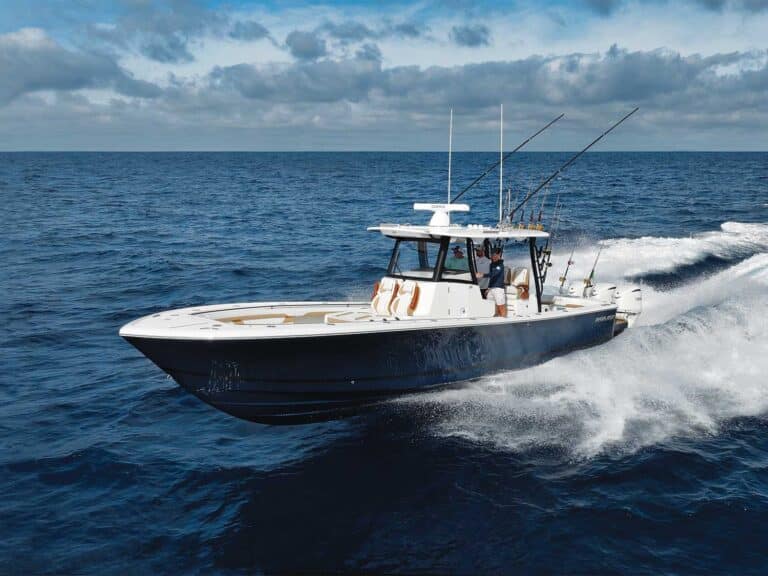

Monique Richter began painting faux teak about four years ago. In addition to transoms and toe rails, any traditional teak accents are prime for faux, she says, including helm pods and chair backs on the bridge, or interior items such as trim and tables. Center-consoles are increasingly being fauxed also, including outboard cowlings.

Besides just replicating real wood on boats, Richter employs wood-grain faux as art—the beauty of wood grain accentuating obviously nonwooden objects. “I was really just messing around, creating something to post on Instagram,” Richter says, when she painted a Yeti cup as if it were a black-and-white-photo rendering of teak. Since then, both natural wood grain and that grayed-teak look have made it onto mailboxes, coolers, golf carts, an automobile and a full-size RV touring bus.

“The faux itself has appeal as art,” she explains, “It’s something different—completely custom—and people choose one-of-a-kind items that will stand apart from anything else.” Richter is currently fauxing a 45-rod set—everything from spinning rods to gaffs—in grayed teak, a pink-toned rocket launcher that will benefit breast-cancer awareness at auction, and a teal blue teak-grained Yeti cooler to help fund autism research.

In a sense, faux is capturing the appeal of the handcrafted art adorning mass-produced, everyday objects. That is not unlike the way real teak adds a custom, artisan touch to fiberglass boats.