The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has recently been cracking down on the enforcement of the Ship Strike Reduction Rule, which is a set of regulations protecting endangered right whales. Several of my clients have recently received certified letters from NOAA with associated fines up to $20,000 for violating this rule. As a result, it is important for captains and owners to be familiar with the regulations, as well as the applicable zones and the apparent methods of enforcement.

Dates and Times

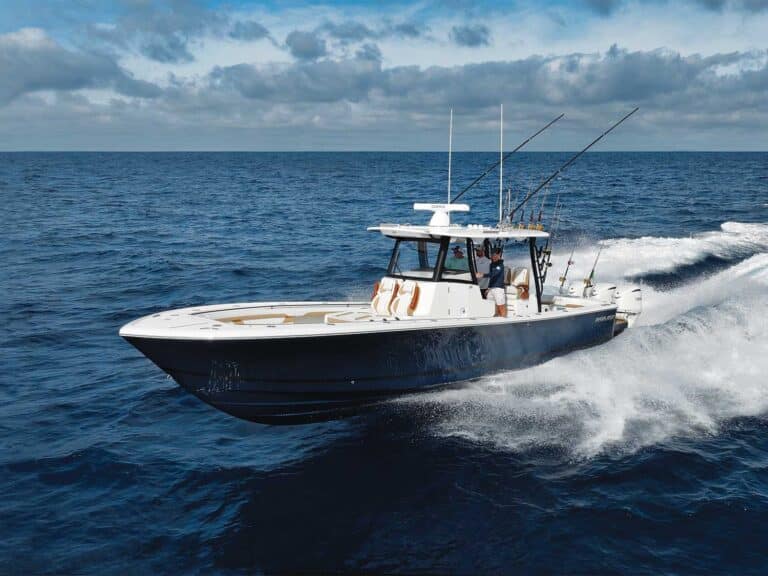

The rule is promulgated under the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and is specifically in place to prevent vessel collisions with right whales. It states that all vessels greater than or equal to 65 feet in length must slow to speeds of 10 knots or less while underway in the northeast United States, mid-Atlantic and/or southeast seasonal management areas, which are thoroughly defined in the code of federal regulations. The rule applies in the mid-Atlantic management area from November 1 to April 30 and from November 15 to April 15 in the southeast management area. The northeast U.S. area has differing timelines in the winter and spring between Cape Cod, Race Point and the Great South Channel off Massachusetts.

The Zones

The location of the zones in the management areas are too specific to fully cover here, but they can be reviewed on NOAA’s fisheries website. Generally, the areas cover certain locations and zones at specific points along the East Coast from Massachusetts to northern Florida, all of which include waters close to shore. For example, the mid-Atlantic area includes a 20-mile radius outside of the New Jersey and New York ports, the port of Beaufort, North Carolina, and the entrances to the Delaware and Chesapeake bays. It also includes a body of water outside Block Island Sound and a continuous area of 20 nautical miles from shore between Wilmington, North Carolina, and Brunswick, Georgia. It appears many of the vessels in this area are likely caught in violation of the rule while transiting south for the winter.

Fines and Enforcement

Most first-time violators receive a reminder letter from NOAA, which provides an overview of the regulations. However, repeat violations usually result in fines, which can reach up to $100,000 in severe cases. The biggest fine we have seen is $20,000 for a repeat violator. As of early August 2019, we were receiving letters from NOAA regarding violations from November 2018, so NOAA must have quite a few letters to send. I should also note that I am not sure how NOAA handles a vessel that has multiple violations prior to receiving the initial reminder letter.

The letters from NOAA provide little information on the location of said violations and the speeds at which the vessels were traveling, which leaves many owners wondering how they were caught. Enforcement techniques have not been confirmed but it certainly appears NOAA is using automatic identification system information to locate and track boats in violation of the rule, which for most of us seems like a questionable tactic.

Using AIS

Operating in the VHF mobile maritime band, AIS is an automated tracking system that allows vessel operators to monitor marine traffic in their areas. Generally, it acts as a navigational aid and provides information such as the name, position, course and speed of each vessel in that area. It appears NOAA is now also using the technology to enforce the rule, so vessel operators should be aware of the relevant zones because they might be freely transmitting their information with unintended consequences. Admittedly, I was fairly uneducated on the rule until a couple of months ago. I knew of right whale zones and I had seen them on various GPS units, but I did not know the specific consequences of violating the rule. It came as a surprise when we started receiving calls from various owners and captains who had received certified letters and fines from NOAA. I urge all large-vessel operators on the East Coast to familiarize themselves with the rule and the methods of enforcement.

Raleigh P. Watson is a contributing author, and a Partner at Miller Watson Maritime Attorneys.