In the highly competitive boatbuilding world, one brand stands above all others. The resilience of the Rybovich name has been spotlighted, stripped, rehashed and reborn many times throughout the decades, but the true story has never been spoken. From the inside, I discovered that truth is usually stranger than fiction. For those who ever wondered: “What’s the real story?” I put on a hat I never thought I’d wear, and braced myself for the fallout. Turns out, Michael Rybovich appreciated the journalistic effort and answered every one of my questions without objection.

Considering the difficulties boatbuilders go through, you can’t help but appreciate the superior craftmanship that makes up a Rybovich; no wonder they are the epitome of what we imagine a Palm Beach 10 to be. I have been lucky to work on several of these boats—two 53s, a 55 and a 62-footer—and the service at the North Yard was always top-notch. A slew of white shirts waited at the slip for your arrival, were there at your departure, and if you owned, ran, or worked on a Rybo, you were treated like a king. But in those days, the lucky few who were privileged enough to be associated with the finest rides sport fishing had to offer were also deserving of them.

It takes a special person to work on a Rybovich, and as one captain plainly put it: “When you roll up on the nicest boat in the marina, you better be extra-pleasant, because everyone automatically assumes you’re an a**hole.”

“To paraphrase an old cliché, I was born with a silver name in my mouth,” says Michael Rybovich, grandson of John “Pop” Rybovich Sr.—Palm Beach, Florida’s own Rybovich and Sons’ legendary carpenter and entrepreneur. “It’s like being Frank Sinatra’s son: The first time you pick up that microphone, you should be able to sing better than anyone else, or you’re considered an imposter.”

Born of eastern European immigrants, John Rybovich Sr. was a hard-working carpenter and self-taught fisherman who rose in the face of defeat. In the 1920s and 1930s, there was no shortage of catastrophe, including the September 1928 hurricane that devastated his modest waterfront property and the Great Depression settling in. The booming bootlegging business had kept the family fed and clothed during Prohibition; the rum runners even perhaps helped to steer the solid and fast boats Rybovich was—and would be—known for. Soon, big-game sport fishing was beginning to carve its way into American culture, and Pop began making modifications to the Palm Beachers’ power cruisers at a good clip.

As World War II came around, Pop lost his free labor when Tommy and Johnny were drafted and Emil volunteered. Luckily for Pop, military contracts that had him converting pleasure craft into patrol units kept the business together. By the time the brothers returned from the war, each was armed with newfound skills thanks to Uncle Sam—and each had a role in a company that had been nurtured by their father. It was game on.

Sport fishing was a new concept in the 1940s, when Palm Beach Chevrolet dealer, C.F. Johnson was eager to obtain a boat worthy of pursuing giant tuna in the Bahamas. He placed his trust in Rybovich and his sons, and in 1947, the first Rybovich—34-foot Miss Chevy II—was delivered, complete with all the trimmings: outriggers, fighting chair and a promised 20-plus-knot cruise—built for $35,000.

Growing Up Rybovich

The thick Slovak-accented voices of Michael’s grandparents were a constant in his young life. Pop and Mom Anna lived modestly on the waterfront property, but Pop had little tolerance for the young ones, running them out of the yard—right into Mom’s warm, hugging arms. She’d fill the kid brothers’ bellies full of mangoes and cookies and send them right back to the yard to find their father, Emil—and Pop would run them out again. “She was the sweetest person I have ever known,” Michael recalls of his grandmother.

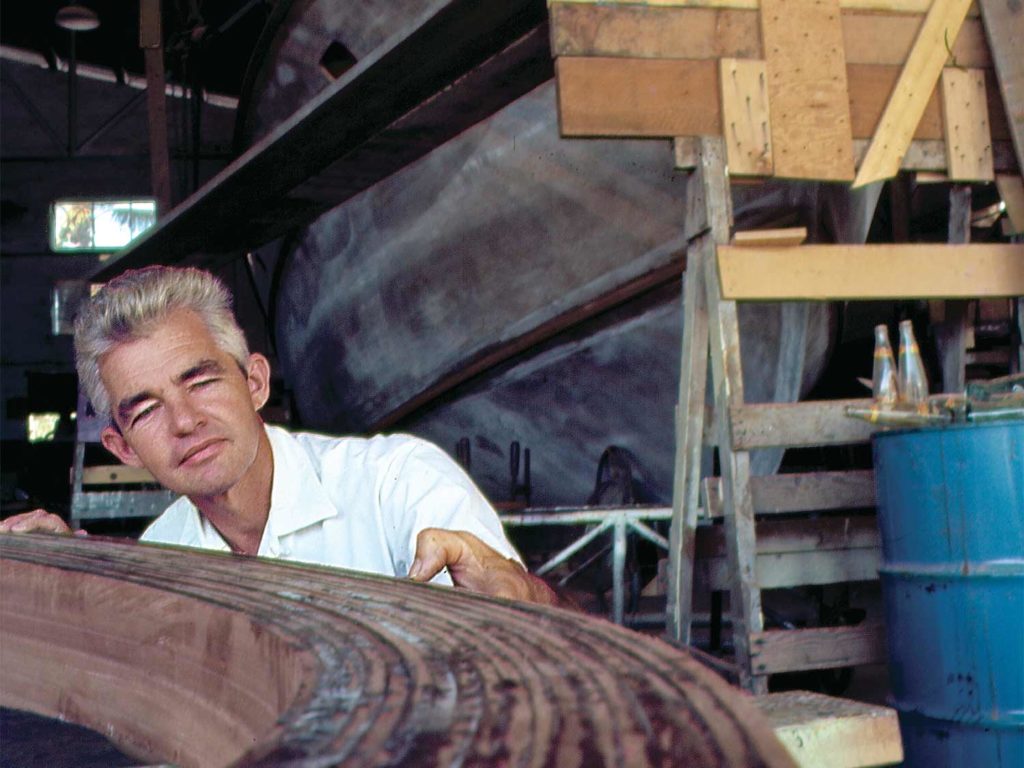

When Michael was a little older, he and his brothers—Marty Evans and Tom—were tasked with picking up soda bottles, each earning two bits at day’s end. “We grew up at the yard,” he says, “and on weekends, Dad would bring us there to keep an eye on us.”

Surprisingly, Michael’s parents never steered him toward boatbuilding. He was to go to college and make his own career path, or so he thought. “I had no real plans to join the family business before my first day on the job,” he says, “but something clicked, way down deep.”

Boats were never his only love—music was too—and Michael eventually figured out that rocking it out four or five nights a week and working a six-day week at the yard was virtually impossible. “Boatbuilding won the battle of careers in my heart; I put away the music,” he says. And after that, he couldn’t help but answer the proverbial calling. He couldn’t get enough of it.

“I earned my first boatyard paycheck after I joined the bottom gang in early 1975 working for my Uncle Johnny, who had a reserved and serious presence,” he continued. His bottom crew referred to Johnny as “the Whip,” and when you were told something needed to be done, it had better be done.

While Michael’s father was more eager to impart what he had learned from Pop, who died in 1970, his Uncle Tommy, a quiet, dedicated artist, had also died by the time he started working for the business full time. Tommy Rybovich—an envelope-pushing, stubborn perfectionist—was the designer and chief builder of every boat that came out of the yard until his 1972 death of lung cancer at 52.

“My Uncle Tommy was the soul of that place,” Michael remembers, “out-working the rest of the family and every single one of the employees.” And while Emil and Johnny struggled to maintain the Rybovich standard, it soon became an impossibility.

“The work ethic Tommy set forth couldn’t be duplicated,” Michael says, and after 79 hulls, the company was sold to Bob Fisher in 1975—the first of four owners not bearing the Rybovich name.

Shift and Change

Fisher insisted Johnny and Emil stay on to run the company, initially giving the family the right to continue using the Rybovich name, saying everything would remain the same. But after watching many employees find jobs at other yards and clients seek repairs and new projects elsewhere, Johnny found he could no longer defend the new owner’s business model. Four years of mental exhaustion caught up with him, and he left the only home he ever knew. Emil followed in 1980, and Michael became the head boatbuilder.

He managed to survive the change in ownership for the next nine years despite the surrounding antagonism brought on by multiple organizational changes, as well as his own disappointments. Michael left the company in 1984 to form Rybovich International with his father, brother Marty, and family friend Ed Bussey; Gary Hilliard became his replacement.

Now called Rybovich Marine Services, the original company was sold again to another owner in 1986, and it wasn’t long after the last of the Ryboviches left that they were attacked—their name smeared by the pure arrogance of the new owner—and they were forced to sign a consent agreement, which forbade them from not only using their own (brand) name “Rybovich” in any business endeavors, but also banned them from building any boats with their signature double handrail or broken sheer. It was devastating.

The International team was slapped with a lawsuit by the now expanding Rybovich Marine Services. “I wanted to fight the bastards,” Michael says of the new owner, “but Dad advised against it, saying all the family’s assets would go up to combat a battery of Philadelphia lawyers, literally.” In retrospect, he agrees his father was probably right, and says whenever they disagreed, it all seemed to work out eventually. But it took a lot of time.

In the wake of a lawsuit and even more hardship, the family agreed to drop the use of Rybovich and decided on Ryco. “Marty and I figured it was as close as we could legally get, and it would be right next to Rybovich in the phone book,” Michael says.

As Rybovich Marine Services and the Spencer yard merged in 1991, a whirlwind of expansion began and Rybovich-Spencer was not only building boats, it was also servicing some of the most exclusive yachts in the world. Fortunately for the brand, Hilliard, a brilliant shipwright who had worked on the new hull crew with Michael under Emil and Johnny, continued the Rybovich tradition of boatbuilding, completing another 14 hulls at Rybovich-Spencer—operating on the same piece of property Pop bought in 1919, just north of Ed Bronstein’s Spencer boatyard.

By 2004, the Huizenga family owned the property and the name. The largest yacht yard in South Florida was now called simply Rybovich.

Looking to revisit the possibility of getting his name back, Michael approached H. Wayne Huizenga Jr. and explained to him the timeline of events and how pretension and spite created an almost 20-year absence of Ryboviches building Ryboviches. “Realizing the silliness of it all, and through the goodness of his heart, Huizenga gave us back the right to use our own name,” he says, “and to him, we are very grateful.”

“Realizing the silliness of it all, and through the goodness of his heart, Huizenga gave us back the right to use our own name, and to him, we are very grateful.”

Michael teamed up with Huizenga to start a boatbuilding division at his soon-to-be superyacht marina after Hurricane Wilma destroyed the Ryco yard in 2005. Although the partnership started with good intentions, the recession that began in 2007 affected everyone. The stock market plummeted, boatbuilding screeched to a halt and the partnership was forced to abandon the venture.

In the spring of 2010, Michael left the Huizengas—name intact—in search of a place to re-establish his Rybovich brand. With the help of longtime friend and multiple Rybovich boat owner Larry Wilson, Michael and his wife, Julia, purchased the old E&H Boatworks site from Andrea Hodge.

“We hit the ground running,” Michael says. “There aren’t many gals who would agree to spend every last cent on starting from scratch in your mid-50s,” he continues. “I am very lucky to have Julia by my side.”

The Long Haul

As a private business owner, much less one who is celebrating his family’s 100 years in boatbuilding, Michael has found change is crucial to keep the ball rolling.

Now the reigning patriarch of a brand that could have so easily slipped through the cracks, his own three sons—Dusty Rybovich, and Blake and Alex Gill—are ready to carry the torch for a family that not only has been through the wringer, but has bounced back when practically every door was slammed. The sons are preparing for what the future might hold for the brand. By keeping open minds and exploring their options, they will be better-equipped to overcome the obstacles this industry will inevitably throw at them.

A growing shortage of qualified shipwrights and skilled carpenters, painters, mechanics and electricians present another bump in the boatbuilding road. Coupled with a decline in the quality hardwoods that Rybovich and his sons very much rely on and an ever-changing customer base, the family has a long row to hoe, but realistically, these things have been a part of the custom-boat industry since its inception.

A single sign hangs in one of Michael’s construction bays that reads: Every job is a self-portrait of the person who does it. Autograph your work with excellence. And the shipwrights at Michael Rybovich and Sons autograph theirs with pride.

Rybovich is a brand that has hung on to employees for decades—seeing one another from bachelorhood to grandparenthood.

They’ve helped carry on the tradition by building legendary boats that are recognizable from afar and stand out in a crowd. The loyalty of the people who have followed Rybovich throughout all of its variations, from one end of Palm Beach County to the other, is evidence of the builder’s ability to instill a work ethic beyond measure—exemplifying quality, excellence and commitment.

The family still believes that there is certainly a name-recognition factor associated with their boats, but, “There is also an appreciation for owning something of the highest attainable quality—a piece of what started it all—completely handmade that begins with the selection of rough timbers in a remote lumberyard and ends with a ride on a 40-knot-piece of fish-catching furniture,” Michael says. As his father Emil used to say, “In the end, it’s all about pride of ownership.”

Each one of the current set of Rybovich sons is talented in his own right, bringing a knack and ability to pick up where the previous generation left off. “I have been blessed with a well-rounded team,” Michael says, “with the strengths similar to Dad, Johnny and Tommy. I am grateful that the Divine Admiral deems us worthy to continue this into the fourth generation, and I know my sons are up to the task.”

Get to know Michael Rybovich in our exclusive interview.

How does the company plan to keep the legacy on course for the next 100 years? Michael believes “the only proven approach to longevity and success involves blood, sweat and tears. Simply put: you have to live it 24/7.” And they do.

At the end of a gravel road, on the side of a waterfront building in Palm Beach Gardens, the “and Sons” portion of Michael Rybovich and Sons harkens back to a time when your name was all you had. And even though hard times have been a constant in the lives of the Ryboviches, they continue to persevere. Michael is confident his sons—the ones who are paving the way for the next hundred years—will be known for sharing their innovations and solutions also, just like their ancestors before them. May the legacy continue.

Michael Rybovich’s Favorite Rybovich?

Little Pete—a 58-footer built for Paul Leviton, completed in 1972. “That was Tommy’s last build,” he says, “and although he did not live to see the completion, Little Pete was the largest at that time; and to this day, one of the prettiest, low-profile boats we ever launched.” As a young boatbuilder, Michael would take walks down the south dock to check that his own work on another vessel matched the high standard of what Tommy had accomplished: “Capt. Joe Moore always had her looking like a supermodel and welcomed my visits—shoes off please.”