As a child I spent the summers on our boat at Rudee Inlet in Virginia Beach, Virginia. I remember winning the kids bluefish tournament and leaving the dock at midnight to take a 12-knot cruise to the billfish grounds.

Every August, teams would fill up Fisherman’s Wharf and the Virginia Beach Fishing Center for the Virginia Beach Marlin Tournament. It was during those Labor Day weekends that I developed a palate, if you will, for Carolina boats. Sportsman’s Carolinian, Irvine Forbes’ My Boy and the boat that stole my heart, P.D. Gwaltney’s No Problem. I didn’t know then that each was a marvel and that I, as a small kid and later as a fish-crazy teenager, was witness to history in the making.

I say that No Problem stole my heart, but it could have been her owner. Woody Woodington, still flirtatious today at the age of 91, was boisterous and joyful. No Problem was unlike the other Carolina boats of the day. Her sweeping sheer line and black rub rails made her look like she was going fast sitting right in the slip. Down below, she was a feat of engineering, the first of her kind and the springboard for technology that only today is starting to reach its full potential.

I asked Woodington if it was the boat’s composite hull and cold-molded engineering that prompted his purchase back in 1980, and he said, “Darlin’, when a man buys a boat, it is a love affair.” Woodington claims he saw her picture on the cover of a magazine and that was it. Then he went on to recount fishing stories, and brag about the boat’s twin 8-92s and nimble 27-knot speed. “We did some whoopin’ that summer, but the next year we were the ones getting whooped,” Woodington says.

Pioneers

Speaking of Pilfering

Omie Tillett once told me the easiest way to build the boat you want is to measure all the boats you like. No need to reinvent the wheel when your heart’s desire is staring you right in the face. He proved that one when Warren O’Neal built Sportsman in 1961. Her cabin design and sheer line were stolen right from the Rybovich boats of the day. As it turns out, the local boys farmed the Florida boatyard for more innovations during the next decade. While Buddy Davis was adding strength to his hulls by diagonally double-planking, as was the norm at Rybovich, Billy Holton was taking notes while the builder fooled around with a jig. “I went down several times in the early 1970s,” explains Holton. “It took a bit to wrap my head around it, but I finally got it.” From that borrowed beginning, the Carolina jig boat took off without looking back.

A Different Point of View

“You will never believe this,” says Sunny Briggs, “but I came around the corner one day and found Billy Holton standing on his head outside his boat shop.” “Oh yeah,” says Holton. “I had to stand on my head to get my mind around it.” Well, there you have it.

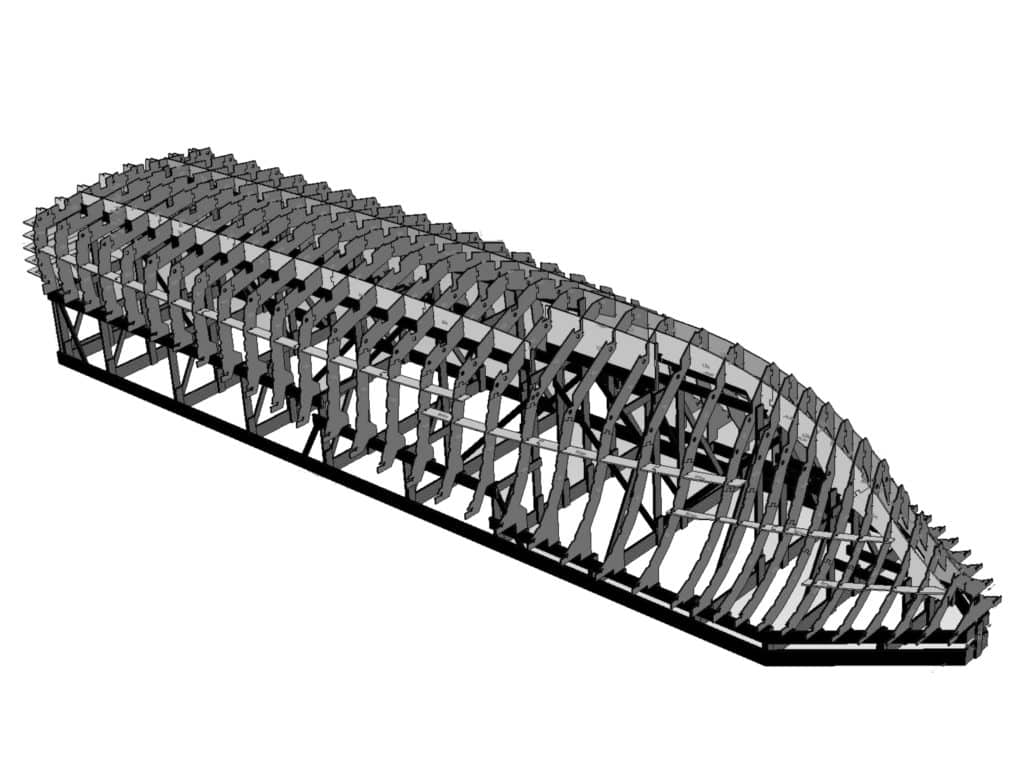

Holton built the first Carolina jig boat in 1976. His first jig boats were 32 feet, cold-molded with plywood, unlike those of the Rybovich team, which used mahogany laminates. At the time, builders still depended on rock of the eye to set up the jig. Holton learned the trade with O’Neal, Tillett and Davis but was influenced just as much by his stepfather, Sheldon Midgett. Father-in-law to Paul Spencer, and “Papa Shel” to the family, Midgett’s story is still being weaved today by the innovations at Spencer, where pushing the boundaries of jig building seems to be the norm.

“I had two shops back then,” explains Holton. “I messed around with jigs in one and built plank-on-frame in the other. I built my own jigs and actually built jigs for other builders as well.” Holton goes on to explain that plank-on-frame was the standard of the day, and the debate had already started over what was the better boat. That is a war that still wages today, but there is no denying that the jigs of today are more modern and precise. “The aids and computers make building the jigs efficient and exact,” adds Holton.

Innovations Abound

“Of course, I had more knowledge of the plank-on-frame boats because I had worked for Omie and Sheldon, but when it was time for my own boat, I could see that jig building was a better way,” says Spencer. “I know the general public is slow to come around sometimes, but I am not quite that way.” From underwater exhaust to pods to composites and resin infusion, the Spencer family has proved it is not afraid of innovation. “If I work it out, do all the research and groundwork, and I feel like it makes sense, then I will try it,” Spencer says.

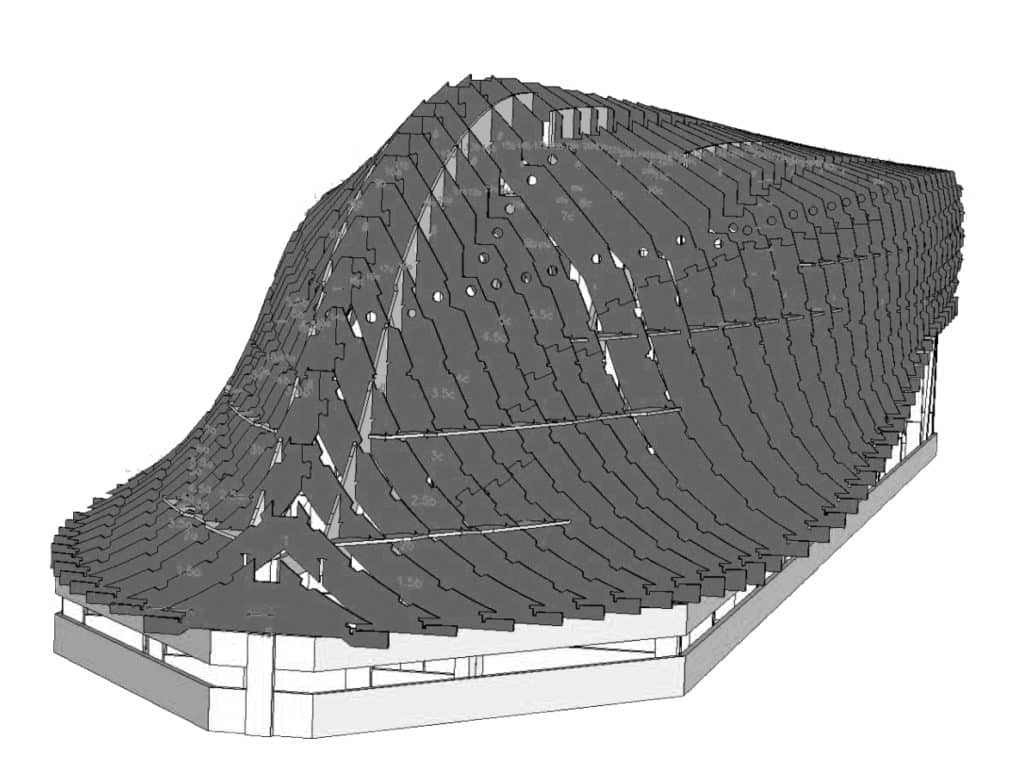

As we talk about the history of jig building, Spencer touches briefly on digitizing and cutting the jig, but what I believe captures his imagination is the use of Corecell composites. His eyes light up, and he begins to talk a bit with his hands. “P.D. Gwaltney was one of the first people to use Corecell and polyester,” Spencer explains. “That was the very beginning of the improved techniques and technological advances.”

A Little Bit of Genius

Reading Gwaltney’s memoirs, on loan from his son Steve, opens a door into the mind of a boatbuilder who was never satisfied. If P.D. had only been blessed with bottomless pockets, I am certain Gwaltney Boats could have rivaled Boeing for innovations in composite construction.

“Airex wasn’t available in this country back then,” explains Holton. “It was one of the first composite materials, and P.D. had it shipped here from England. I built jigs for him, and we talked about the building process and how to place stations, etc., but he was on his own with the composite materials.”

Gwaltney admits in his papers that all of the revolutionary techniques he tried cost a bundle to see through. “All of these better ways of building are actually rocket science,” says Spencer. “They start there and then go to the airplanes. Eventually we can afford to implement them on our boats.” The Gwaltneys tested fiberglass instead of plywood for the outer layers of their sandwich construction, the first full composite-only construction, and they experimented with weights on their panels, resins and even vacuum bagging.

“All Gwaltney boats since the 47-footer were built with the idea to make them as lightweight as possible, while at the same time making them strong enough for offshore rough waters,” Gwaltney wrote. “Contrary to normal boat construction, the internal runners, floors, bulkheads, beams, carlings, decks and stringers were their strength. The hulls we laid up, although strong, were designed to keep the water where it should be, on the outside.” Gwaltney boats were designed to do more; all of the parts and pieces had to be lightweight, strong and in the right place.

While the Gwaltneys were well on their way to revolutionizing composite building, Davis was busy as well. In 1980, he tried his hand at jig building, and told me once before he died, “I just didn’t like it.” Just four years after Woodington fell in love with No Problem, Dare County saw the realization of Davis’ dream and his first plug and full-hull mold. The innovations in molding hulls were not lost on Gwaltney. He respected the strength and integrity of the molded hull but still frowned at the weight. The builder continued his quest for the best sandwich-construction process and worked his way through composites such as Airex, Klegecell and Divinycell at various densities, as well as roving glass, glass mat, Kevlar fiberglass roving and Fabmat.

High-Tech

It Was Dee’s Idea

There are those who will argue a plank‑on-frame boat is stronger and those who are vehemently opposed to that view, but rare is the man who believes jig building is less efficient. “How do you test the strength of a hull unless it fails?” says Ricky Scarborough Jr. “And how often does that happen in either form of construction? But there is no denying that jig building is a better way. Not a better boat, necessarily, but a better way. I think it is more of a business issue than a strength and integrity issue.”

And Scarborough’s opinion has merit. He learned to plank-and-frame at his father’s feet, then taught himself how to use a computer and purchased a CNC router for their interiors. He now uses that router to cut his jigs. “Plank-on-frame requires more skill to build, and that limits you as a builder,” Scarborough explains. “In jig building, the skill comes at the drawing phase.”

Classic Lines

The computerized hull designs were the last piece in the Carolina jig boat puzzle. In 1991, the industry was once again revolutionized, and that particular milestone has captured the imagination of builders all over the globe.

“We used to loft our own hulls,” explains Briggs. “We built our own jigs. I started jig building back in 1986 with some 37- and 45-footers. Before that, we built plank-on-frame.” Briggs had a call for a new build back in the early 1990s but didn’t have the time to build the boat. It was his wife’s idea, during a discussion over dinner, that put the industry on its ear. “I was eating supper, and she was washing dishes,” Briggs says, “and she said, ‘Why don’t you call your buddy Steve and send him your drawing; he just has to find a way to cut it out.’”

At the time, Steve French and his company, Applied Concepts, had been making some interiors, but never a hull. “Applied Concepts deserves all the credit, but the whole thing was Dee’s idea,” says Briggs. “Bob Sheldon got his boat, and it was just like clockwork. We didn’t talk about it much back then; we weren’t trying to keep it a secret, but we didn’t brag on it either.” Nearly three decades later, little has changed about the process Briggs and French developed. “That first CNC cut was within 3,000th scale,” Briggs explains. “It was closer than any saber saw.”

The computerized jig has allowed for a more efficient build, and many builders save even more money refining their materials list. “I only order one extra sheet of plywood per layer for my hulls,” Briggs says.

Computer Aided

Looking Ahead

Gwaltney used a John Deere tractor to drag steel plates onto his sandwiched Corecell panels; the pressure of the weight created a stronger bond as the resin kicked off. These days, vacuum bagging has replaced steel plates and tractors. I watched workers at Spencer Yachts setting up the cabin mold for a 59-footer with Corecell sandwiched between layers of fiberglass. In a few days, those layers will undergo 28 pounds per square inch of pressure during the resin-infusion process.

I’d like my Carolina jig boat with a side of rocket science, please.