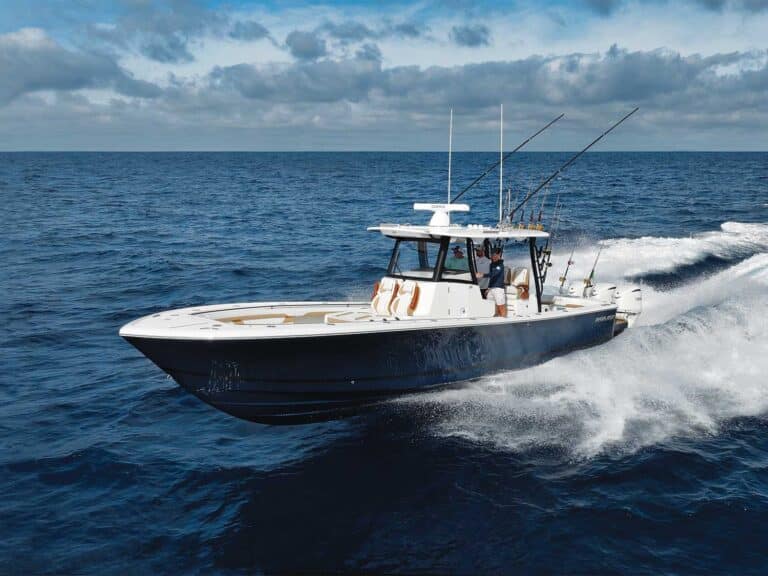

I remember riding on a 31-foot Bertram during one of my first offshore-fishing trips—I was getting soaking wet in the pre-dawn Texas darkness, my feet wedged against a cooler filled with J-hook-rigged Spanish mackerel and silver mullet, and we were going marlin fishing. I was thinking, This is the greatest day of my life! and at the time, it was. Nearly 50 years and millions of man-hours later, billfishing in the Lone Star State has undergone an evolution that none of us could have imagined. From gasoline-powered boats with paper depth recorders and loran-C to 80-plus-foot sport-fishers with GPS, omnidirectional sonar, a dozen or more tuna tubes, and crews who can fish day and night for extended periods, it’s been a hell of a ride so far.

The impetus for the early pioneers of billfishing in Texas can be traced back to two defining events: the Tarpon Roundup in Port Aransas, Texas, in 1932 and the Texas International Fishing Tournament, founded in 1933 in Port Isabel. Capt. Kirk Elliott, a member of the Draggin’ Up team, says: “Over the years, the boats were able to pack on more fuel, had more range, found cleaner water, and began to find more pelagics.” And there, the story begins.

The Tarpon Roundup was started by a handful of guides in Port Aransas as a friendly competition among themselves, as well as a way to promote hunting and fishing in that part of the state. Over the years, it transitioned to the Deep-Sea Roundup to be more inclusive of all aspects of the local coastal resources of the bay as well as nearshore and offshore waters. The Texas International Fishing Tournament—known throughout the state simply as the TIFT—was founded almost simultaneously by Dr. JA Hockaday in 1933 to promote the pristine waters of the lower Rio Grande Valley to anglers from all over the state, and eventually the world. Elliott says: “When I was 8 or 9 years old, I rigged baits in Port Aransas for 5 cents apiece, everything from mullet and Spanish mackerel for the offshore guys to ribbonfish for the nearshore fishermen. We didn’t have loran, only a compass, so when we went offshore, we would line up with the Brown & Root industrial plant’s smoke stacks in Port Aransas and head due south. When we almost lost sight of those stacks, we were at Hospital Rock, and eventually we ventured another 10 miles farther out to the East Breaks.”

The First Texas Blues

One of the first people to mention the existence of blue marlin in Texas was S. Kip Farrington Jr. in his 1949 book Fishing the Atlantic, where he stated that a number of blues were caught off Port Isabel, with the largest being 326 pounds, caught by JR Montgomery of Rio Hondo, Texas. There was also a mention of three boats that caught 21 sailfish among them in three days off Aransas Pass. The first true offshore oil platform in Texas was called Mr. Gus; built in 1954, it was short-lived when it sank off Padre Island in a storm in spring 1957 after just a few years in service. Due to the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act in 1953, as well as the federal government’s restrictions and subsequent lawsuits over leasing rights in the Gulf of Mexico, offshore platforms were put on hiatus. That didn’t stop the early pioneers from pursuing their marlin-fishing passions from some of the most famous Texas boats such as Cora Bell, Pancho Villa, Zapata, Wolverine, A Boat Named Sue, Red Label and Blue Streak, all plying the waters off the middle coast at spots including the East Breaks, Hospital Rock, Dutra and Colt 45. Loran-C, paper recorders, single-sideband radios and radio direction finders were showing up on more boats, which also continued to get bigger with each passing year. In 1960, the first Bertram 31 prototype won the Miami-Nassau race in 8-foot seas and 30-knot winds; it went into full production the next year. A decade later, Bertram started producing the 46, which became a benchmark for offshore boats in Texas to better handle the prevalent 3- to 5-foot seas and 15- to 20-knot wind conditions. Other builders such as Hatteras, Post, Ocean, Rampage, and many others would change the face of offshore fishing in Texas and around the world.

A New Era Begins

The 1960s and ’70s ushered in a new era of billfishing in the Lone Star State with names such as Babe Appling, Joe Bright, Bob Byrd Sr., Stewart Campbell, Jack Elliott, Walter Fondren, Capt. Bill Hart, Preston Stofer and many more being the vanguard advancing the sport to new levels. In 1969, Fondren, Bright, Byrd Sr. and Campbell founded the renowned Poco Bueno tournament in Port O’Connor, which grew to become the premier marlin tournament in the state during its zenith, attracting boats and crews from all across the Gulf of Mexico and around the world. Tournaments mean money, money means competition, and competition breeds innovation, which really helped elevate offshore fishing in Texas.

Louisiana’s Capt. Roger Greene and Byrd Sr. of Texas are credited with being some of the first fishermen to experiment with lures in the Gulf. Greene met Henry Yap in Louisiana in the early ’70s and bought some of his taper-head lures from Kona; Greene had tremendous success fishing with Tommy Faust and later, Archie Lowery. Byrd Sr. had traveled to Kona in the early ’70s, fishing with Capt. Bart Miller on his charter boat, Black Bart; Byrd Sr. brought some of Miller’s techniques back to Texas. Capt. Terry Burton on Cazadora says: “Boats started using lures more in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but not without significant trial and error. We were using 14/0 and 16/0 hooks in our lures and missing tons of fish. Miller gave us a tip during a Poco in the early ’80s, saying that our hooks were way too big, that we needed to use 10/0 and 12/0 hooks and lighter leaders. Our hookup ratios really started to increase once we made the switch.”

Byrd Sr. and Capt. Bill Hart started hitting their stride in the late ’70s, along with Campbell and Capts. Bark Garnsey and Peter B. Wright; the crews started pulling lures, covering more ground, and refining their techniques with exceptional results. One of the early lure innovators in Texas was Jerry Dunaway, Capt. Skip Smith and his crew aboard The Hooker. Working with Frank Johnson of Mold Craft fame on a Hooker prototype softhead lure, the team known as the Texas Terrors came in second at the Poco with the largest fish of the tournament; they proved that their success was no fluke by winning the whole thing on a Mold Craft Hooker lure the following year. The payout of $300,000 for first place was an unheard-of amount of money for any fishing tournament in the world, putting Texas and lure-fishing squarely on the world’s sport-fishing map. Little did we know what was just around the corner.

The Rigs Return

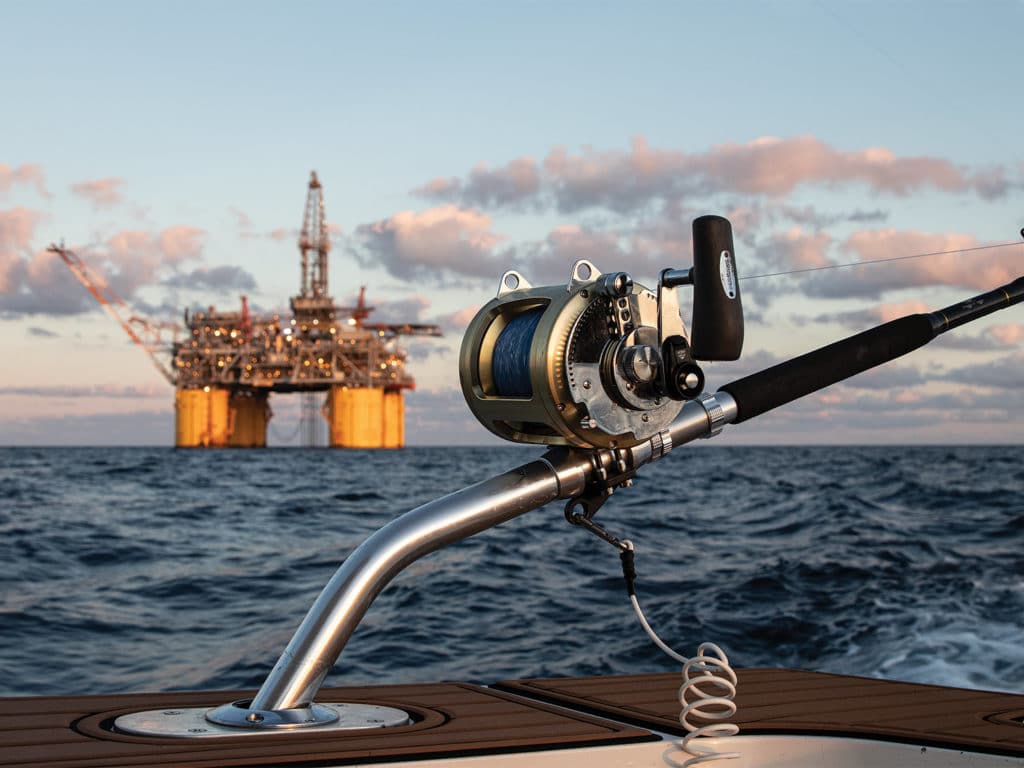

The early 1980s kicked off a boom in the oil business: The twin Cerveza rigs were installed in 1981 and 1982, Tequila in 1984, and Little Sister in 1985, all being on or beyond the 100-fathom line and in prime territory for all types of pelagic species. The primary method of marlin fishing in Texas went from trolling bottom structure to “ring around the rigs” in the relative blink of an eye. In the mid-’80s, it was not unusual to see a dozen boats circling the rigs on a calm weekend; during tournaments, that number could easily double. These vertical reefs concentrated the bait in small areas that were accessible to boats and crews of all styles and preferences, using dead bait, lures, and a technique that many had not experienced in the past: live bait.

Capt. John Cochrane, who passed away as this issue was going to press, said: “When I came back from Australia in 1980, I was running the 37-foot Merritt Billy B out of Freeport for Bill Lyons. We fished almost exclusively live bait around the rigs because that’s all Bill wanted to do. I remember fishing with Capt. Mike Canino in the early ’80s on a 46-foot Post named Abra-Ca-Dabra, watching the Billy B team live-baiting with a kite for the first time in my life.” Smith says that Garnsey and Wright live-baited with Campbell in the early ’80s, adding, “We live-baited at the Cerveza [rig] in 1986 during the Poco and won second place, but I know we probably weren’t the first to weigh a fish on live bait.” Over the years, the live-bait technique would prove to be deadly effective.

The second wave of ultra-deepwater rigs installed in Texas—Hoover-Diana in 2000, Nansen in 2001, Boomvang in 2002, Gunnison in 2003 and Perdido in 2009—not only doubled the amount of productive locations to fish, but also sent live-baiting into a whole new stratosphere.

In 1987, Dr. Mitchell Roffer introduced Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service, which used a combination of satellite imagery, oceanography, and recent fishing reports to produce detailed analyses of Gulf of Mexico surface conditions to help predict pelagic migrations and areas where fishing would be the most advantageous. ROFFS was a game-changer. I remember going to the marina office or even to the public library to get the ROFFS charts, which were sent to us via fax machine. They didn’t necessarily tell you where to fish, but they definitely told you where not to go.

The Game Continues to Change

The introduction and widespread use of tuna tubes in the early ’90s really helped the live-bait fishery become more mainstream and allowed the crews to fish all day instead of mostly in the mornings and evenings, when the bait was easiest to catch. In 2004, Tom Hilton brought the fishing world into the digital era with his Hilton’s Real-Time Navigator, which combined sea-surface temperature, altimetry, chlorophyll, salinity and currents, along with rig and floater locations. Hilton says, “Our website allowed subscribers to find overlapping favorable conditions in multiple intersection areas, which greatly increased the odds of finding the target species on a recurring basis.”

As more crews started live-baiting on an everyday basis, their techniques also became more refined. Using lighter fluorocarbon leaders, multiple tuna tubes with spa pumps that were much easier to regulate, plus the familiarity of rigging live baits again and again made a huge difference. Most mates could grab a bait from the tube and have it rigged and in the water in less than 30 seconds, which substantially increased the odds of the bait staying healthy and active, therefore increasing the odds of getting a bite. The 2008 National Marine Fisheries Service regulation requiring recreational fishermen on Highly Migratory Species-permitted vessels to use circle hooks with natural bait or natural-bait/artificial-lure combinations during tournaments increased the catch ratios for live-bait fishermen. The Hawaiian-style drop-back with a large loop of slack line between the rigger clip and the reel, which allowed the marlin to swallow the bait without any resistance, upped the catch ratios even more.

Capt. Jason Buck of the 92-foot Viking A Work of Art says that Capt. John Uhr of Chupacabra and Seay Goddess fame was a devout live-bait fisherman, but the emergence of sonar also added to the evolution, becoming one of the most powerful tools at any captain’s fingertips. Buck was the former captain of John Gonsoulin’s Done Deal, a team that had tremendous success fishing throughout the Gulf, with an enviable slew of tournament victories to their credit. These guys are good and were winning before sonar, but Buck said that they had the first Furuno CSH8L sonar installed in a sport-fishing boat in the Gulf. He says it took nearly two years of trial and error for him to truly adjust, understand, and interpret the displays, and he credits Capt. Steve Lassley of Bad Company fame and Furuno technician Steve Bradburn with really helping him fine-tune the unit to give him confidence in its performance. He laughingly told me that they were on a rip following a huge mark that they worked for 30 minutes that refused to come up. He told the mates to break out the downrigger to send a bait deep when suddenly the mark started coming to the surface. That’s when he saw the huge head of a 500-plus-pound leatherback turtle emerge from the water behind the boat. Sonar tells you there is something down there, but it sure doesn’t tell you what it is or if it will bite.

Read Next: Get to know some of the photographers who have contributed to the unique look of Marlin over the years.

The proof of the effectiveness of live-baiting the deepwater rigs in Texas was never more evident than with the capture of the Texas state-record blue marlin, which was caught by George Gartner’s Legacy team in 2014 during the now-defunct John Uhr Memorial Billfish Tournament, otherwise known as the Bastante. Capt. Kevin Deerman, mate Cameron Plaag, Colin Ocker, Jeff Owens, Michael Fitzpatrick, Reuben Ramos and I were live-baiting the Hoover-Diana Spar on the first morning of the tournament. I had the first bite of the day at 6:55 a.m., and after a down-and-dirty 15-minute fight, our team sank the first gaff, although it took another 45 minutes to finally get the fish secured. The tail was touching the starboard side of the 56-foot Viking, and the bill was just a few inches short of the port side. We put the tape on the fish, and to our amazement, the short length measurement was 137½ inches, with a 74-inch girth. When it was finally weighed at tournament headquarters in Rockport by weighmaster Bud Kittle, the fish registered 972.7 pounds, a new Texas state record by almost 100 pounds. That fish is also by far the most memorable blue marlin of my fishing career to date.

Looking ahead, it’s clear that the evolution of marlin fishing in the western Gulf will continue to advance as technology emerges and the times change. Building on a solid bedrock of past traditions, it’s going to be interesting to see just how far we can go.