Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives. Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter.

The concept of affixing something to an animal that allows humans to track movements and gain information is not new. For centuries, we’ve furthered our understanding of animal behavior through such methods. Atlantic salmon were the subject of some of the earliest fish-tagging efforts, with documented tagging dating back to the early 1800s in Scotland.

+By the mid-1900s, conventional tagging programs for billfish had popped up in various parts of the world. These were largely limited to small research groups and fishery-management agencies, until The Billfish Foundation launched its Tag and Release Program in 1990. TBF’s program made billfish tagging mainstream and capitalized on growing sentiment within the industry to move away from the routine harvest of billfish, catalyzing a paradigm shift in big-game fishing culture. Tag sticks quickly replaced gaffs, crews adapted their techniques and tackle, and many tournaments subsequently restructured their rules and scoring. TBF’s conventional tagging program made conservation cool.

Since the program’s inception, TBF reports having received more than 260,000 tag-and-release forms. And they aren’t the only ones. While TBF’s program receives the most exposure, there are several other prominent groups around the world that conduct large-scale conventional tagging programs for billfish and tuna. With thousands of submissions filed every year, conventional tagging by recreational anglers continues to produce important data regarding growth rates, migratory patterns, habitat utilization and post-release survival rates. All of this, of course, helps to better inform policymakers and better protect billfish.

Yet despite its popularity and value, conventional tagging has its limitations. While its simplistic design lends favor to its widespread usage, the data provided by conventional “spaghetti” tags is limited to point-to-point location and estimated growth. Conventional tagging also presented the major obstacle of having to recapture the tagged fish to receive the data. Intrigued and hungry for more information, scientists, researchers and anglers began looking for new technology to answer the questions that conventional spaghetti tags could not.

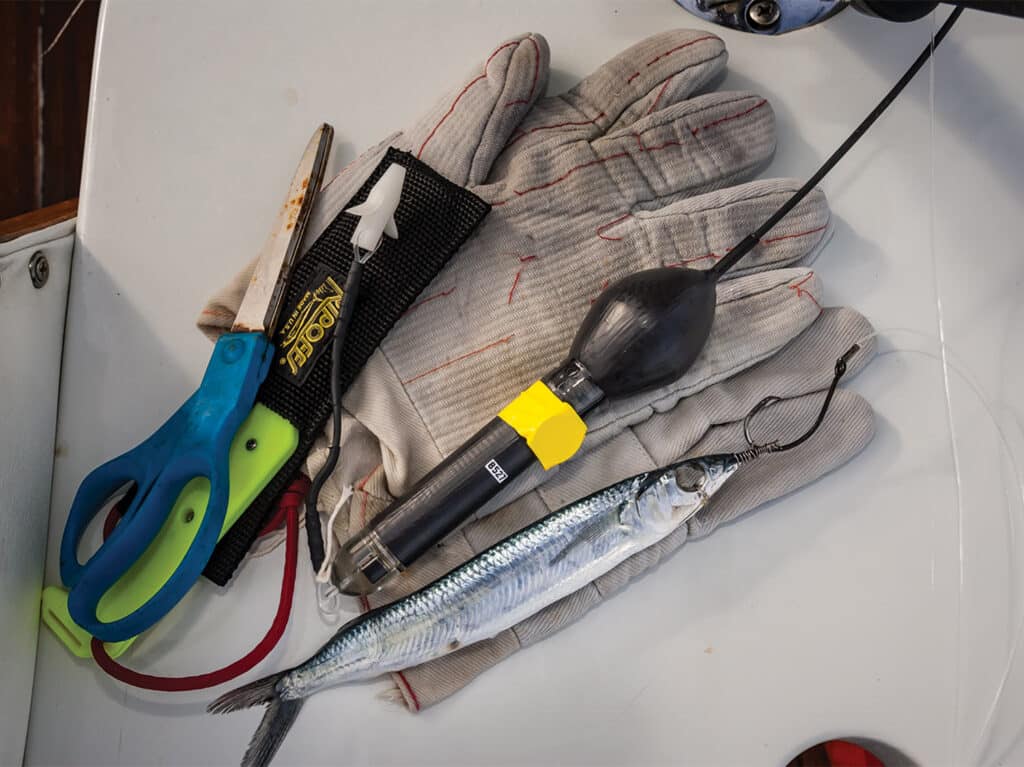

This paved the way for the development of the archival tag. Used extensively for studying tuna and other marine life, archival tags are microprocessor data storage tags that are implanted inside a fish. Archival tags collect vastly greater data than traditional conventional tags, including the geo position of the fish (more accurate tracks), thermal physiology (temperature data) and diving behavior (depth). However, archival tags still presented researchers with the crippling limitation of requiring the recapture and reporting of the fish to retrieve the data. Enter the pop-up satellite archival tag (PSAT).

The PSAT

In 1998, a team of scientists led by renowned marine biologists Barbara Block and Eric Prince published a paper titled “A New Satellite Technology for Tracking the Movements of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” in which they documented the first-ever successful deployments of PSATs on wild bluefin tuna. Fishing with legendary captains Peter B. Wright and Gary Stuve off North Carolina in 1997, Block and her team successfully deployed 37 first-generation PSATs on bluefin tuna. Armed with a release mechanism programmed to automatically detach after 90 days, the tags achieved a remarkable 95 percent success rate, proving that PSATs could in fact work for wild pelagic fish. While similar to the implanted archival tags in its engineering and data-collection capabilities, the PSAT distinguishes itself from traditional archival tag technology by eliminating the need to recapture the fish (tag) to obtain the data. Once deployed, the tag collects data until the preprogrammed release mechanism corrodes, allowing the tag to float to the surface and upload the collected data to a satellite, which then transmits the data to researchers.

Shortly after her success with bluefin, Block led a team in deploying the first PSATs on billfish during the 1997 Hawaiian International Billfish Tournament. Following subsequent years of successful deployments and growing interest among anglers, the International Game Fish Association formed a partnership with Block to create the IGFA Great Marlin Race. For more than a decade, the IGFA Great Marlin Race has been a global leader in the satellite tagging of billfish. Partnering with Block’s renowned lab at Stanford University and working directly with recreational anglers, the program has deployed 606 satellite tags that have provided invaluable data to further our understanding of billfish behavior and life history. Perhaps the most valuable aspect of this project is that all data gathered is “open access,” meaning it is free and easily available for scientists.

Similar to how omni sonar, gyrostabilizers and Starlink have changed the world of big-game angling in recent years, satellite tags have too been game-changers in how experts track and learn about billfish. “We had no idea these fish do what they do before PSATs,” says Julian Pepperell, acclaimed marine biologist and leader in billfish, tuna and shark research. “Sure, we had an idea from the conventional tag data, but when we saw the tracks from the first PSATs, it shocked us all.” In addition to learning about the impressive large-scale migrations these fish undertake, the less “sexy” data captured by the PSATs also provides enormous insight to researchers. “The PSATs expanded our knowledge of diurnal depth patterns across all pelagics, which is very important in interpreting catch rates of various species,” says Pepperell. “And understanding the temperature preferences of these species will enhance our understanding of adaptations they are making to climate change.”

Fruits of Your Labor

Walking the docks during any major billfish tournament, you’re hard-pressed to find a boat that does not participate in tagging fish, or isn’t at least familiar with tagging programs. We spend billions of dollars chasing these fish around just to stick a tag in them, but why?

For decades, recreational anglers have contributed invaluably to our present knowledge of billfish, yet many are not aware of how impactful their efforts have been. “We started conventional tagging research in Australia with the New South Wales Fisheries Department in 1973,” recalls Pepperell. “We now have records of over 170,000 billfish tagged through this program, with thousands of submissions entered every year. This data, and the research that has come from it, provide fishery managers with valuable information to assist in stock assessments, and therefore create effective management plans. Without the data we don’t know what we have.”

And the list of benefits does not stop there. “One of the greatest by-products of PSATs is the value they’ve provided in studying post-release survivability rates among billfish and other marine life,” Pepperell explains. “For example, the research that John Graves did on white marlin, which demonstrated significantly higher post-release survivability with circle hooks than J hooks, was made possible by PSAT technology.”

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed into law the Billfish Conservation Act (BCA), which closed commercial markets in the US to foreign-caught Pacific billfish. Before that point, the US had been the single largest importer of billfish in the world. President Donald Trump strengthened the law in 2018 with a technical amendment stating that no billfish (marlin, sailfish, spearfish) can be entered into trade in the continental US, regardless of where it was caught. Spearheaded by the IGFA and Wild Oceans, and supported by other groups, this groundbreaking legislation has been applauded by industry leaders as the most significant event for billfish conservation in history. Tagging data was a crucial component of the compelling case presented before the US Congress to make this all happen.

What’s Next?

Since Block’s first-generation PSATs were deployed off Cape Hatteras in 1997, several modifications to the original design have improved performance and functionality. Perhaps the greatest advancement has been the increased length in which these tags can remain attached to the fish, collecting data. Compared with the first-generation tags that were programmed for 90-day deployments, modern tags are now recording tracks in excess 240 days.

However, aside from longer track times, there haven’t been any monumental advancements with PSAT technology in recent years. “We haven’t had any major leaps with PSATs to address some of the limitations, including their size, the duration they can remain on a fish, and probably most importantly, the cost,” says Pepperell. “We need more data from satellite tags, but at the current cost, averaging around $4,500, it’s extremely prohibitive to research. Usually technology gets more affordable with time, but we have not really seen that with PSATs yet.” Looking ahead, Pepperell is optimistic about the possibility of longer deployments, stating that a vault of one- or two-year tracks would be the Holy Grail in terms of learning more about different stocks of fish and the return of fish to natal spawning grounds. In other words, we still need more data.

Luckily, the major leap that Pepperell and others have been working toward may be just around the corner. According to him, new tag anchoring systems are being tested that could potentially be more durable, allowing for longer deployments and more robust data recording. Funding for research on marlin, sailfish and spearfish has always played second or third fiddle to more commercially important species like tuna and swordfish. Recognizing that, conservation groups have taken matters into their own hands to help fund billfish research. The IGFA recently launched the Billfish Research and Conservation Endowment, in 2023, with an initial seed of $3 million that will continue to grow and be used solely for billfish research, in perpetuity. While that is a good start, at the end of the day, it’s the data’s application that truly makes a difference.

Bruce Pohlot, IGFA conservation director, heads up the IGFA Great Marlin Race. Pohlot’s extensive tagging experience put him on the front line of PSAT evolution and how better data is the key to informed management. “The true benefit of any tagging effort is not necessarily the data they produce themselves but what scientists can do with that data,” Pohlot says. “For long migrations we are able to link each location the fish sends with environmental and oceanographic data to build a database of information. This database can be analyzed to determine behavioral traits relative to environmental characteristics, which helps us better understand the drivers of billfish movements and preference for certain conditions.” Pohlot also mentions larger plans that have been discussed among researchers that would use this data to help address commercial-fishing pressure. “With better data we can predict where those conditions billfish favor will overlap with commercial fisheries, and map out where billfish might be most vulnerable to bycatch.”

The “database” Pohlot refers to is another concept that many marine experts are advocating for, a global collaboration to compile all available tag data, for all marine species, under one roof with the goal of developing more precise marine ecosystem modeling. After decades of groups independently tagging fish around the world, this would be a colossal undertaking, but certainly one worthy of further consideration.

Read Next: A Young Angler’s Journey to Help Billfish Conservation Efforts with Satellite Tagging.

Tagging has forever changed the world of billfishing and is a prime example of how those closest to our resources oftentimes do the most to protect it. And while there are some unknowns as to what the future holds for tagging, one thing is quite certain based on history: Regardless of what the engineers and scientists churn out next, there will be no shortage of anglers eager to stick it on a marlin.

Tale of the Tracks

To illustrate the groundbreaking information made available by PSATs, we’ve employed the help of Marlin contributor and IGFA conservation director Bruce Pohlot to analyze two impressive billfish tracks from the IGFA Great Marlin Race.

Lizard Island Track

One track from the IGFA Great Marlin Race reigns supreme as the longest distance from deployment to pop-up ever recorded. At the 2014 Lizard Island event in Australia, Ernesto Bertarelli’s sponsored tag was deployed on a giant, 1,100-pound black marlin. After just 180 days attached to the marlin, this tag popped up 5,716 nautical miles from the deployment location, nearly 1,000 nautical miles farther than the current second-place recovery. This marlin is estimated to have traveled a total of 6,787 nautical miles along its migratory track that heads east away from Lizard Island toward the eastern Pacific before the tag popped off about 1,800 nautical miles west of South America and less than 300 nautical miles southwest of Easter Island. This is one of the largest black marlin tagged using a PSAT, and the resulting track is truly incredible. Given the lack of recreational fishing in the open Pacific, this result would only have been possible using a satellite tag.

Big Rock Track

This blue marlin, tagged during the 2023 Big Rock Blue Marlin Tournament in North Carolina, undertook a remarkable migratory path as one of the only IGFA Great Marlin Race blues to travel from the Atlantic into the Gulf of Mexico. The fish leaves the area offshore of North Carolina, travels to the Bahamas and back, and then swims through the Straits of Florida into the Gulf of Mexico toward the Yucatan Peninsula before returning through the Straits to Cay Sal Bank. It then doubles back again to the waters off Belize before the tag pops off the fish after 240 days, 1,169 nautical miles from where it was deployed. Overall, this fish swam an estimated total distance of 5,654 nautical miles. Additionally, this 300-pound blue spent approximately 40 percent of its time within 33 feet of the surface, where the water temperature ranged between 77 and 86 degrees. The deepest dive occurred in mid-September to a depth of 1,739 feet, where the water temperature was 52 degrees, the coldest water experienced during the deployment.