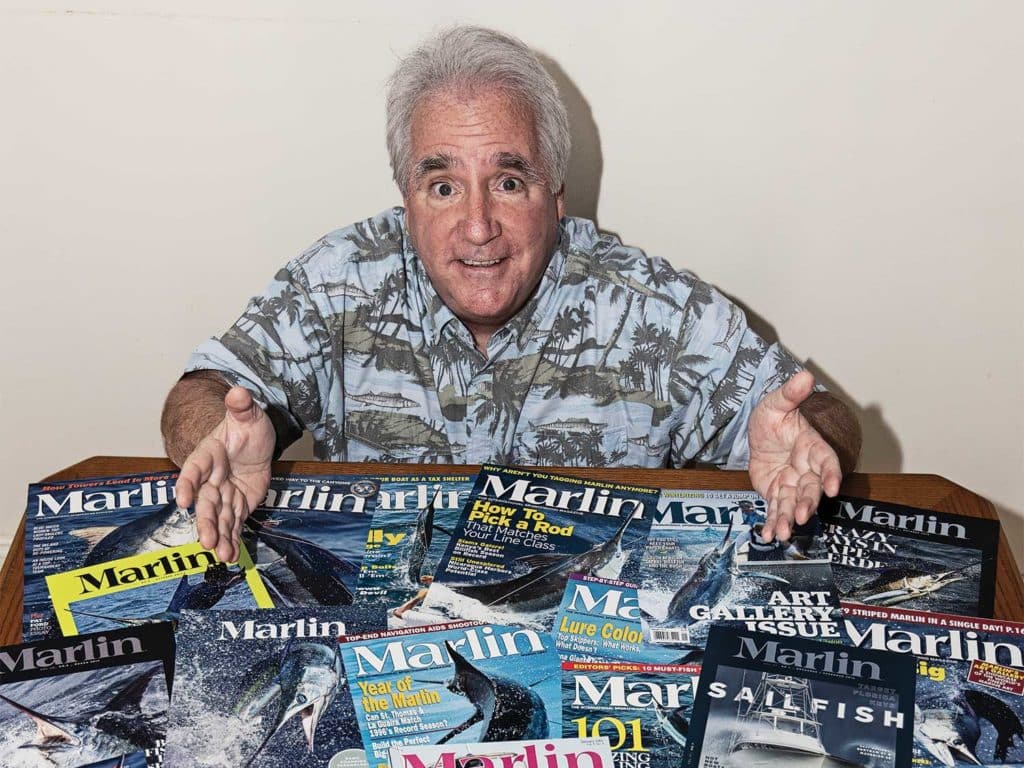

As a journalism major at Morehead State University in eastern Kentucky during the late 1970s, Richard Gibson landed a part-time job as a photographer for the school’s newspaper; the experience taught him that a career in news and sports photography was his calling. After graduation, Gibson went to work as a staff photographer for the Virgin Islands Daily News in St. Thomas, where he covered the annual marlin tournaments; it was his first exposure to the world of offshore sport fishing. With 58 Marlin covers to date—and counting—Gibson is still looking for that next great shot.

Q: What was it like to fish the North Drop back in the 1980s and early ’90s?

A: Spectacular! There weren’t too many traveling boats yet, and with so little pressure on the edge, it led to some amazing numbers of nice fish every day. I quickly became friends with the local captains and crews, most of whom fished the Drop year-round. Red Bailey invited me to ride along with him on Abigail III, which I did as often as I could, sometimes in pretty damn rough conditions. I learned two clear lessons the hard way about fishing and photography: Salt water always wins; and if it can possibly fall, it will. Fortunately, SLR cameras weren’t too expensive in St. Thomas back in those days—I replaced quite a few.

Watch: We show you how to rig one of the best baits for blue marlin: the swimming mackerel.

Q: You were at the Virgin Islands Daily News for seven years—favorite memory of that time?

A: In July 1982, I was in the darkroom and got the call that I needed to get down to Red Hook as soon as I could because there was a potential world-record blue marlin on the way in. I jumped in my Volkswagen Thing and zoomed to the east end of the island as fast as it would go. Once I got there, I found Capt. Joe Lopez’s 43-foot Merritt, Prowess, backing into the dock with what turned out to be the women’s 130-pound-test world-record blue marlin, which was caught by Annette “Maudi” Lopez. Only problem was she had a 16/0 J hook completely through her ankle. I followed Maudi’s ambulance to the old St. Thomas hospital, and then with her back to the dock where they weighed her fish: 1,073 pounds. It was an IGFA record that stood for more than three decades.

Q: Your early work was shot on slide film. What was that like?

A: I believe what separated me from other photographers in the early years was quite simply that I could focus. The early professional SLR cameras were 100 percent manual everything, but my experience as a daily shooter sharpened my skills in ways that included being able to produce tack-sharp images of jumping blue marlin. And the North Drop didn’t disappoint either, with plenty of opportunities to shoot fish. Magazines such as Marlin required color slide film, but the problem was that all transparency film speeds were very low. Sharp focusing was challenging enough, but then freezing an acrobatic fish with a high shutter speed was almost impossible with film speeds that low. Luckily, Kodachrome 200 came out and allowed shutter speeds up to 1,000th of a second in bright light, which was a real game-changer. By comparison, these days I’ll shoot fish at 8,000th of a second with my Canon EOS-1D X Mk II.

Q: Where did you catch your first blue marlin?

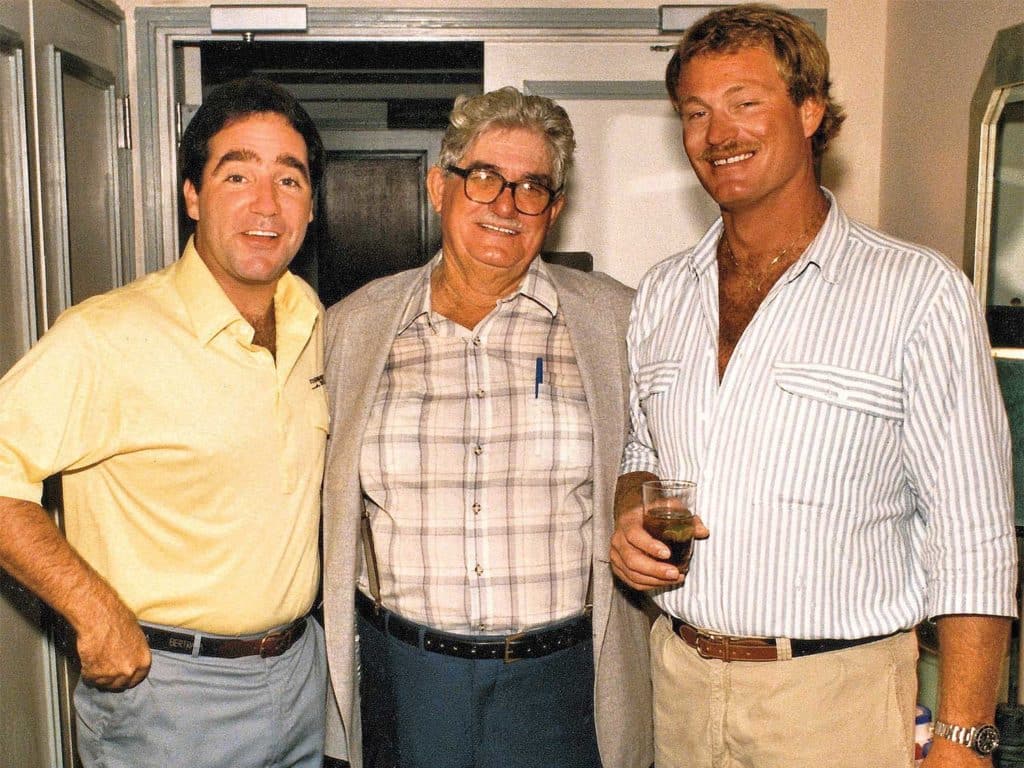

A: I left the Virgin Islands in 1985 to become managing editor of Tournament Digest magazine. This new publication reported on billfish tournaments worldwide, and while it was plenty of work, I also loved being part of this exciting world of big-money events. It enabled me to travel the world—twice—to just about everywhere major offshore tournaments were being held. That’s when I caught my first blue marlin, during the 1986 Bertram-Hatteras Shootout in Walker’s Cay in the Bahamas. I was able to experience the virgin fishery in Costa Rica before any American boats were there, plus the rest of Central America, Venezuela, Africa, Australia, and the East and Gulf coasts of the US. If there was a major tournament there, I probably was too at one point or another.

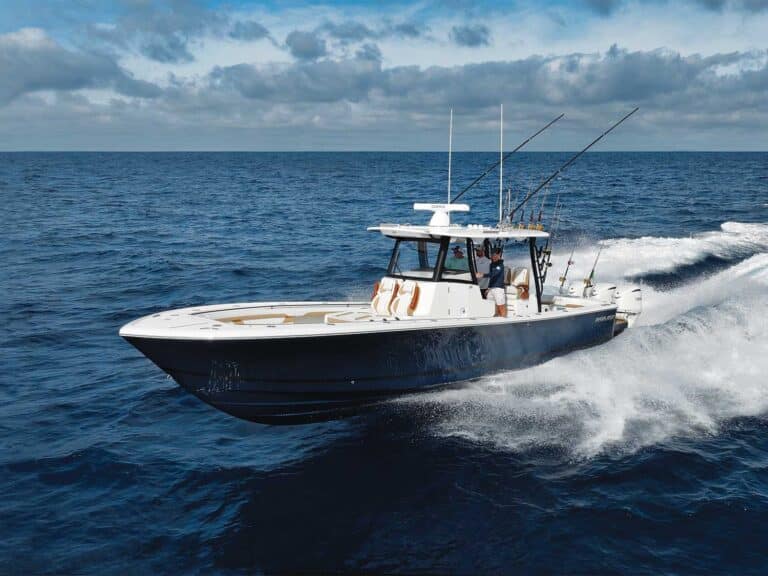

Q: Any other advantages?

A: A big one was that we also had access to a new 54-foot Bertram called Free Enterprise, and the boat’s exceptional schedule, which included all of the great billfish destinations of the time. Winter sailfishing in Palm Beach, then down to Cozumel, Mexico, in spring. The full moon blue marlin season in St. Thomas, then to Venezuela in fall. The jumping-billfish photo opportunities seemed nearly endless, and I became great friends with the boat’s skipper, Capt. Randy Jendersee. He and I are still close friends today, all these years later. We were both young back then, the beer was cold, the fishing was epic, and life was pretty good.

Q: Any close calls?

A: Back in the early ’90s, I decided to try my luck with underwater offshore photography, and the Yucatan Peninsula seemed as good a place as any. I was with Capt. Tony Davis, who was running a G&S named Anastasia in Cozumel. One day, while trolling across the channel to the mainland, we hooked four blackfin tuna, so I asked if I could jump in and shoot some photos. Camera pressed hard against my mask and concentrating on the fish, I felt a powerful swipe on the back of my right leg. Thinking I had drifted into the side of the boat, I surfaced to frantic shouts of “Shark!” from Tony and all on board. They pulled me back into the boat just as a 500-plus-pound mako proceeded to eat one of the blackfins right beside us. All the hair and most of the skin on my leg had been sanded off by the mako as it went past me, and to this day, I don’t understand why it didn’t bite me. There was another time where I was holding the leader and shooting a sailfish that I thought was worn out. Well, it suddenly came back to life and speared me in the face, putting a hole the size of a dime in my upper lip just under my face mask. I got the message that time—that was the last of my undersea photographic adventures.

Read Next: Get to know some of the other photographers who have contributed to the unique look of Marlin over the years.

Q: Where do you go from here?

A: I just produced my first book of photography called Back “R” Down that I’m very proud of. And the gear will continue to evolve. One thing is clear though: Marlin has truly solidified itself as the world’s premier offshore big-game fishing publication, and I’m certainly proud to have been associated with this powerhouse of exciting stories from today, as well as a small part of its celebrated history.