Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives. Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter.

Few big-game captains have built a legacy as respected as Capt. John Batterton. A native New Zealander, his career has taken him from his home waters and landed him in the heart of angling lore. With his insatiable drive and an instinctive feel for the ocean, Batterton has led with calm confidence and fierce loyalty to his pursuit, earning him unrivaled achievements on the water. In 2024, he received the IGFA Tommy Gifford Award, a fitting recognition for a career defined by quiet mastery. I recently sat down with him in New Zealand to hear his remarkable story firsthand.

Q: How did you first get into fishing?

A: When I was growing up my parents used to fish with a guy named Harvey Franks. I was 6 years old when I went on my first trip with Harvey, and that was it for me. Harvey was a big influence and a big mentor in my early days. I spent a lot of time around him and learning from him. When I got out of school I did a marine-engineering apprenticeship with Sanford—New Zealand’s largest seafood company—but it wasn’t where my heart was. I just wanted to be on the water, fishing. And that’s what I did.

Q: Who were some of your mentors in the sport?

A: In addition to Harvey, Tomo—Frank Thompson on Billfish—was a huge influence early on. I fished with Freddie Rice in Kona, where his son McGrew Rice was also on deck. We’re still best mates today. That time in Kona really shaped how I approach things. Later in life, when we were planning the Hookin’ Bull/Pacific HQ mothership operation, Capt. Skip Smith was a huge help on that front. But I learned something from everyone I’ve worked with, even the bad ones. You learn what not to do, and those are lessons that stick. I’ve had some great mentors, and it is really important to me to try to pass that on to the guys that work for me. I’m still very close with many mates that worked for me, and I always make time to answer the phone when they call. That’s what it’s all about.

Q: How did the Hookin’ Bull operation come to be?

A: Before Hookin’ Bull, I was running a boat called Harlequin out of Bay of Islands, New Zealand. I was just bored of catching striped marlin on 50- or 80-pound gear and was like, “What am I doing?” I started having some success on the light gear, and then I met Guy (Jacobsen), who was even more passionate about the light-tackle game than me. He told me what he wanted to do, and I was all in. From there, it was all about setting ourselves up for success, and having the right boat was a big part of it. Eventually, the whole mothership operation came together. Skip helped us a lot with structure and systems, but when it came to light tackle, no one taught us. We figured it out on our own. We didn’t mind screwing up—we just didn’t want to screw up the same way twice. That’s how we learned, and that’s how we improved as a team. And that’s important to note. It’s often the angler and the captain that get the limelight, but it really takes the entire team to make it happen. The team is what made Hookin’ Bull what it was.

Q: What’s the most challenging record you’ve pursued?

A: That striped marlin on 8-pound was brutal. We weighed seven fish that were within five kilos of the record before we finally got it. On one fish the line over-tested, and two others missed the mark by a kilo. That fish pushed us harder than any other. It taught us a lot about precision—about everything having to line up just right.

Q: You’ve lost records for the wildest reasons. Is there one story that stands out?

A: Even though we didn’t lose it, the story behind Guy’s first 2-pound record for striped marlin was pretty nuts. After landing the fish and a proper celebration, Guy did all the paperwork, everything. A few days later, he calls me and says he can’t find the leader or paperwork. He actually flew us down to his house, and we tore that place apart—went through drawers, cabinets, bags, everything. Nothing. We gave up. Then, a few weeks later, our mothership captain, Tank, opens up a cooler bag, and there it is—record paperwork, line and leader, right under a couple of empty champagne bottles. We were fishing out on the King Bank, ready to catch the same record again, when the call came through that they found it. Needless to say, when we got the news, that 2-pound outfit immediately went back inside the boat. It felt as if we had caught that one twice!

Q: Of all your adventures, what’s the craziest trip you’ve done?

A: Oh, that’s a tough one, mate. The Minerva Reefs were pretty wild. That place is about 250 miles south of Tonga—basically a ring of coral in the middle of nowhere. We weighed some wahoo records there on a lighthouse because there was literally no dry land around. But that said, I think the craziest trip was to New Caledonia, no question. That place is incredible and has some unreal fishing, but talk about being literally in the middle of nowhere. We weighed records on the sand by tying a scale to a tripod. It was like being on the moon. But that wasn’t even the crazy part. Even though we had done all the paperwork and were there legally, we still had French planes fly over and try to chase us out. We had developed a pretty good relationship with the locals there, but we also had a few interesting encounters with them. But I’ll stop there because at some point I would love to get back to New Caledonia and don’t want to burn any bridges! We only scratched the surface on that fishery.

Q: What does the future hold for you?

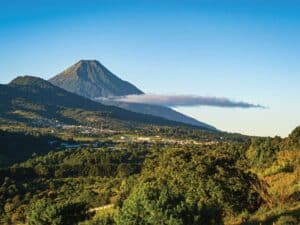

A: I really want to get to 40 world records. I’m sitting at 38 now and have a few in mind. I’d also love to spend more time fishing the Azores. That place just does something for me—huge blue marlin, beautiful water and a classic feel that reminds me why I fell in love with this sport in the first place. I love seeing Pico when I’m headed out in the morning.

I’ve also thought about starting something in Kona. I fished there for years and just love that fishery. The infrastructure’s there, the fish are there, and I think there’s room to do something special. I’m not done yet—not by a long shot. I’m still curious, still exploring, still chasing that next fish.