Big-game fishermen in the United States have been on the forefront of fisheries-management issues for years. The recreational-fishing community has not only been essential in conveying a better understanding of billfish and other pelagics to scientists and policymakers, but it also has been a staunch steward for species conservation.

Special-interest groups such as The Billfish Foundation are hyperfocused on the advocacy for responsible fisheries management, an increase in bluefin quota allocations, and congressional review of federal shark management, as well as issues plaguing the West Coast of the US. TBF’s efforts have helped to realize commercial bycatch-landing reports, the early adoption of circle hooks—several decades before NOAA mandated their use—as well as more than 60 years of traditional and satellite tagging. TBF was also responsible for securing the year-round closed zones in the Gulf of Mexico and off Florida’s east coast to reduce pelagic-longline bycatch of overfished and protected species such as juvenile swordfish, billfish, bluefin tuna, sea turtles and marine mammals.

Watch: We show you how to rig one of the best baits for blue marlin: the swimming mackerel.

The International Game Fish Association, Wild Oceans and others have contributed to the passage of the Billfish Conservation Act of 2012 and its 2018 amendment—a law that prohibits both the importation and sale of billfish on the US mainland and in the Caribbean. The IGFA has also helped lead the way by its own billfish satellite-tagging and tracking endeavors in order to gain the scientific data necessary to back up billfish behavior analyses and conservation efforts. These achievements are certainly admirable, but unfortunately, marine-management issues are not limited to our own bubble; they do, and will, encompass all facets of the industry.

Enter 30 by 30

For decades now, the fishing community as a whole has been subjected to hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of enthusiasm and support fueled by the eco-centrics who take jabs at recreational fishermen. One of those blows is the now-dead Assembly Bill No. 3030—a past effort of California legislation that, according to the authors, would have been added as an act to Section 9001.6 of the Public Resources Code targeted for “resource conservation: land and conservation goals.”

Because of AB 3030’s failure to fully make it out of committee, partly due to fiscal vacuity and stakeholder opposition, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed an Executive Order (N-82-20) on October 7, 2020, “to combat the biodiversity and climate crises” in his state, and to date, this premise is being heavily pursued by the people of California and other activists with an admiration for trickle-up conservation and environmentalism. President Joe Biden quickly mirrored California’s order with his own 7,500-plus-word EO on January 27, 2021, to “take action to uphold [a] commitment to restore balance on public land and waters [and] invest in [a] clean-energy future,” according to a press release issued by the US Department of the Interior, which includes “conserving 30 percent of America’s lands and oceans by [the year] 2030.”

Still, like many environmental issues that start in California, the discourse spreads across the country like wildfire, attempting to place the inhabitants of planet Earth on trial in order to achieve the 30 by 30 goal. Other states have followed suit, but the Golden State continues to campaign almost nonstop for more marine protected areas, even though as of June 2020, 26 percent of all US waters are designated as some form of MPA, and 3 percent are labeled “no-take.”

Mike Leonard, the American Sport-fishing Association’s vice president of government affairs, says that the current administration has acknowledged that recreational fishing significantly benefits the nation’s cultural, economic and conservation objectives, even though there are concerns within the recreational-fishing community that such 30 by 30 initiatives could “be used as a means to arbitrarily restrict recreational-fishing access.” Leonard insists that Biden’s 30 by 30 plan incorporates “many positive strategies for how 30 by 30 should be implemented,” including the absence of language to advise “the pursuit of protected areas in which recreational fishing might be banned without a scientific basis.” While TBF initially opposed the president’s 30 by 30 mandate out of fear that recreational fishing would be marginalized, it hesitantly got on board and intends to work with other organizations to reach a common objective, supporting the idea that any new closures must be credited toward the 30 by 30 goal, making the mandate not as onerous.

Current MPAs include waters designated as sanctuaries, national marine monuments, wildlife refuges and national heritage sites. If the closed zones (such as the waters off Florida, South Carolina and the US Gulf Coast) that still allow recreational fishing but prohibit pelagic longlining are credited toward the 30 percent requirement, then the balance of waters left to be closed becomes much smaller. This would provide closed zones long-term status while still protecting those resources and helping to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change.

The Coastal Conservation Association has been advocating for marine-resource conservation since 1977 and says that anglers are the best stewards of the marine environment, protecting not only the health, habitat and sustainability of such, but also working to protect the access to the resources they enjoy. The CCA understands the importance of habitat, and through its Building Conservation Trust, it has raised millions to restore habitats destroyed by natural and man-made disasters. Some 130,000 members strong, it puts forth the notion that “no-catch marine protected areas do not increase fishery productivity in US waters, [and] no-fishing MPAs should not belong in the US[’s] 30 by 30 plan.”

The CCA also maintains that limiting anglers to public-water access without effectively demonstrating the scientific reason behind the closures undermines faith in the system that ultimately makes 30 by 30 impossible. It acknowledges that some specific situations might warrant variations of MPAs—those that allow catch-and-release fishing under certain circumstances could be beneficial, for example—but rejects the idea that science shows a sound need for more no-take MPAs as a broadly applied panacea.

MPA Studies

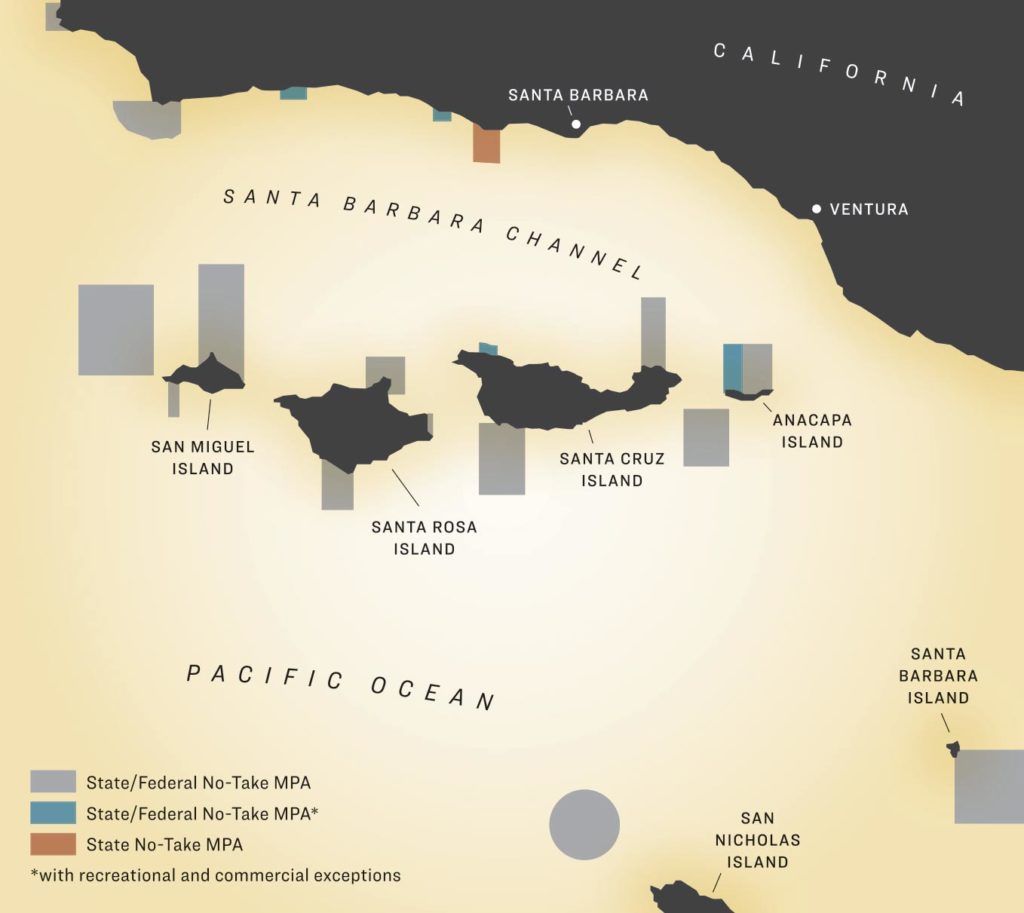

There are a number of scientific studies that have risen to the surface recently, which shed doubt on past claims regarding the actual impact of MPAs, especially when it comes to their effect on the population scale, because they can be harder to detect than we might think. One such study was conducted by University of Washington postdoctoral researcher Daniel Ovando, whose research integrates fisheries science, economics and data science to create practical strategies for marine-resource management. Ovando and his co-authors used a spatially explicit bio-economic simulation model “incorporating core ecological and economic drivers of MPA performance,” together with statistical models, to examine the effects of MPAs in the Channel Islands of Southern California. The results may have been surprising to some, but to those of us who have witnessed MPAs in our own backyards, it was not surprising at all.

Conclusions reached by examining an area in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary suggest that fished species sampled both in and out of the MPAs fluctuated, and that while MPAs are effective almost immediately (after three years), the data showed a probable increase of fish populations inside and outside the MPAs, peaking for three years and then reversing trend in the subsequent years.

Ovando’s conclusions were that “containing a carefully designed, well-enforced, and well-studied MPA network, the Channel Islands seem[ed] to be an ideal location to study the population-level effects of protected areas. But, in contrast to clear differences in biomass densities observed inside and outside well-protected MPAs, both globally (citing Lester et al. 2009) and in the Channel Islands (citing Caselle et al. 2015), we were unable to detect a clear population effect from the Channel Islands’ MPAs.”

Many studies have examined, for example, differences in fish densities inside and outside MPAs after the areas were put in place, e.g., Lester et al. 2009. This is important work, but one of the items Ovando and his colleagues were interested in was whether the effect of the Channel Islands’ MPAs on fish populations existed both inside and outside. To achieve this, the team used a statistical model to compare trends in the total populations of species that aren’t commonly targeted by fishing in the Channel Islands to trends in the total populations of species that are.

While Ovando’s studies found some positive effects of the MPAs on fished populations in the early years, they were unable to detect a clear effect both inside and outside the MPAs in most recent years. This does not mean there wasn’t an effect, just that there wasn’t a clear enough signal in the data to say exactly what that effect was, with the results pointing more toward the challenge of studying the effects of MPAs rather than a judgment about their performance.

Then There’s This

On the global front, the senior editors at the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America—a peer-reviewing publication that has been around since 1915—retracted University of California at Santa Barbara Marine Science Institute’s assistant researcher Reniel Cabral and a handful of his colleagues’ 2020 paper, “A Global Network of Marine Protected Areas for Food.” The essay argued that MPAs designed to reduce fishing pressure would increase world food-source production. The authors, Cabral et al., presented a global model that showed a concentration of proposed MPAs around the US, where little overfishing occurs, but failed to address the overfishing in Asia and Southeast Asia, where it is a real concern when it comes to area food sources and unreliable fisheries data. The model attempted to link global fisheries to regional fisheries

—the Pacific to the Atlantic and vice versa—but fell short when critics took issue with the near-biological impossibility of this connection.

The Cabral paper also touted that if another 5 percent of the ocean were closed to fishing, then fish catches would increase by 20 percent. Max Mossler, managing editor of the Sustainable Fisheries UW project at the University of Washington—whose mission is to “communicate the science, policies, and human dimensions of sustainable fisheries”—says that the “snappy” 5-for-20 statistic made for quite a headline in 2020. However, the higher the ratings, the higher the scrutiny, with many critics pointing out “errors and impossible assumptions that strongly suggested the paper was inadequately peer-reviewed.”

When exposed, Cabral et al. claimed that an older version of the RAM Legacy Stock Assessment database—a worldwide compilation of stock-assessment results for commercially exploited marine populations—caused them to present inaccurate results and “overestimate of the potential food benefit from expanding existing global MPA coverage.” Ultimately, the authors accepted the retraction but maintain that their results are valid and plan to resubmit an updated paper.

It also appears that the person who was in charge of assigning the peer reviews to the Cabral paper, Dr. Jane Lubchenco, collaborated with Cabral et al. as the senior author of a subsequent paper (Sala et al.) that appeared in Nature, using the same flawed MPA model. The PNAS retraction was primarily due to Lubchenco’s conflict of interest, but could these studies themselves (gasp!) be questionable? So much so that it took almost a year to call out the paper’s bluff? The Sala et al. paper is full of inaccuracies as well and is also being challenged, according to Mossler. Lubchenco is now serving as the deputy director for climate and environment at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Retractions in the scientific community are noteworthy, especially by those involved in fisheries management, and even more so when it comes from such a high-regarded multidisciplinary scientific journal as PNAS. Mossler also says that although the conflicts of interest in Cabral et al. 2020 were obvious at publication, it “wasn’t until major problems [and the conflicts of interest] in the underlying science were revealed that an investigation was launched.”

So, yes, the web is tightly weaved. Those in the scientific and environmental communities who present information in bias help to sell an agenda that lacks clear facts and should not be offering up long-term solutions in an attempt to combat problems that might not even exist. Or rather, might have existed but now might not.

Read Next: Learn to make full use of a stand-up harness here.

The Dark(er) Side

For years, lawmakers have been bombarded with pro-MPA materials, but it’s important for them to know that there is a great deal of responsible science that should be, at minimum, considered. But unfortunately, they have continued to do the bidding of lobbyists and appease the doom merchants, diverting their eyes from most other paradoxical views, even though Al Gore’s vehement end-of-times prediction came and went in 2016.

Although Mother Earth is not immune to natural and human effect, she is sure to outlive every single one of us. Our planet has survived at least five major ice ages, one 60-million-year greenhouse period, and asteroid-collision events equaling 350 in the past 10,000 years, according to Australian engineer Michael Paine—including one where an in-atmosphere asteroid explosion wiped out 2,000 square kilometers of Siberian forest in 1908. In reality, the ol’ girl is on track for even more devastation caused by space junk, probably killing thousands and decimating marine-related environments in the next 10,000 years.

When MPA (and generally, environmental) science is examined with conservation in mind, it suggests that there are at least two perspectives with very different goals: One suggests that humans should be separated from nature in order to preserve it, as some advocates of no-take MPAs propose, and the other supports conservation and prioritizes the use of natural resources both efficiently and in a sustainable fashion.

Obviously, no one wants to live in filth or intentionally deplete or contaminate our food, air, or water supply, but I contend that we can protect these resources best if we listen to nonfringe thinkers and consider the findings of those who actually spend time in nature. And so far, recreational fishermen are indeed the better agents to self-police marine resources in the here and now.

Still, the argument is not whether the human race has a responsibility to conservation, but whether the measures meant to protect marine environments and its inhabitants are working. It seems that scientists and national and international governing bodies have dropped the ball in the past, only to have the fishing public’s confidence in them questioned. If we are expected to believe every so-called scientific paper on its face, then the data must be unequivocally transparent and, accordingly, make sense.

Perhaps if Sir Isaac Newton’s Third Law of Motion—for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction—were practiced in other applied sciences, such as natural science, then we might just discover that set-it-and-forget-it no-take MPAs really aren’t a long-term solution to what might be a relatively inherent short-term problem.

It still remains unclear exactly how many marine protected areas will be added as the 30 by 30 movement advances around the globe. Or further, how many of them will include no-take or seriously limit all aspects of fishing, or even if the new closures will be credited toward the 30 by 30 goal. However, scientists must bring into focus factors that aren’t always considered when designating new MPAs—such as fish migration and population, spawning locations, biodiversity, habitat, and human interaction—so that the policies we do place will matter in the long run.