Electronic Strategies

Few captured the trepidation of the anglers of Zane Grey’s era better than he did. Today, myriad tools Grey would have considered magical are available at prices anglers can afford. Many believe these tools make the old skills required for Grey’s kind of fishing obsolete, but in truth, knowing fishing the way Grey did makes today’s magic machines so much more valuable.

Dead Reckoning

The ironic term “dead reckoning” isn’t referring to its mixed and sometimes deadly results. The term instead came about because it was a shortened version of the term “deduced reckoning,” which appeared on charts as “de’ ‘ed reckoning.” Still, the science involves making assumptions, and we all know what happens when we assume.

Historical charts, even those from the 1930s, showed scant soundings, if any at all. Beyond landmarks, many charts held little value for the offshore angler.

So today, you’re heading out to the hump, and while you’re 35 miles from land, the GPS fails. You have your compass, right? Maybe, maybe not.

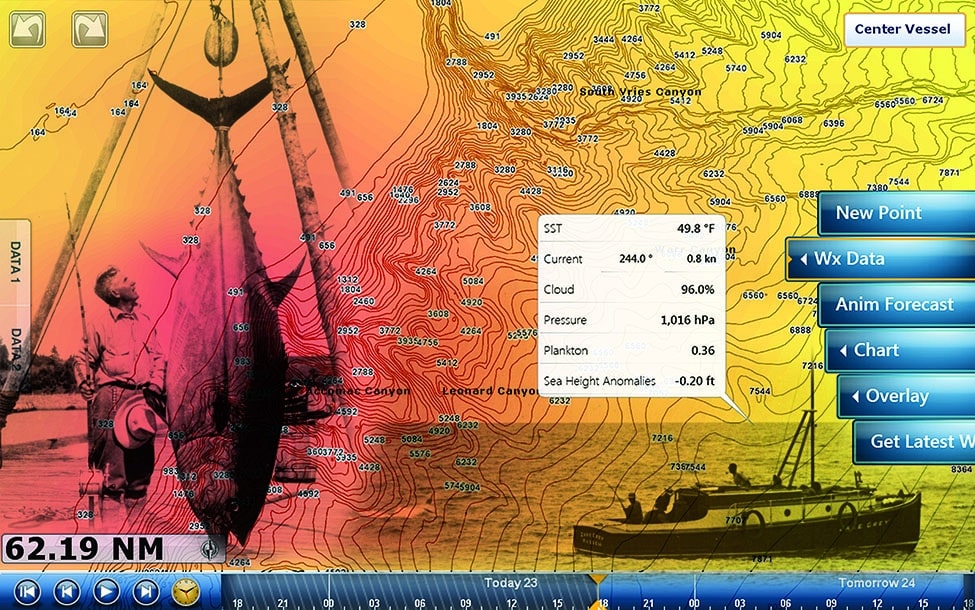

“It wasn’t until the 1970s that captains began to venture outside 20 fathoms,” Mitch Roffer of Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service says. “Before loran, out of New Jersey 20 fathoms was white-marlin territory.” Modern navigation equipment changed all that. Now, tons of data scroll seamlessly across your chart plotter, so you can know to within three feet where you are and what’s under you. You can even do it in the fog.

Brendan Burke of Vero Beach, Florida, is a billfisherman and confidant of Roffer. He began his career before most boats had loran and sonars were the old “white line” machines that gave little more than soundings. He says most captains aren’t prepared to dead reckon. “It takes about an hour to swing the compass,” he says, referring to the process of adjusting a compass’s magnets to minimize error caused by other magnetic fields on the boat. “Lots of times, a stereophile will put huge speakers with giant magnets within a few feet of the compass, and that just wreaks havoc on your magnetic reading,” he says.

Sure, you’ll be relying on your GPS and probably a backup unit, but what about your autopilot? “Most captains never swing the fluxgate compass on their autopilot either,” Burke says. “If they set a magnetic course, they could be miles off when they reach it.”

Bird’s-eye View

“Sometimes fishermen would go along until the water smelled fishy,” Roffer says. “And it did. The tuna would tear into the bait, and the oil from the carnage would surface.”

Oil would slick the surface, and only the smell would tell you if the rip was fishy or just a wind rip.

Roffer says that at other times anglers would look for tuna birds that were known to hang around feeding tuna -— mostly terns and gannets. In the Southeast, anglers looked for circling frigatebirds to point them toward dolphin, sailfish or trophy marlin. Radar can now spot birds for you, but unless you know the lore of how birds and fish interact, you could still be on the wrong track. That’s why top captains — the competitors to beat in major billfishing tournaments — rely on oceanography services like Roffer’s.

X-Ray Vision

Today’s radar is so sensitive it can pick up a coconut on the surface. Navico‘s Broadband Radar or Raymarine‘s Hi Def Digital Radar use high-frequency radars that have no warm-up time and put out such a crisp, short wave signal that their microprocessors can distinguish between a vessel and the tender alongside it. Though digital radar is said to not be capable of showing birds as well as analog’s long-pulse arrays, by dialing down the sea clutter and cranking up the gain until the screen mottles, birds just out of sight can appear as darker marks on the screen.

Long-pulse arrays, however, reveal birds masterfully. The longer signal strikes a stronger echo than the digital versions. Even with it, it takes the knowledge of an experienced angler to tell if the marks are “tuna birds,” like gannets or terns, or birds following dolphin and billfish, like frigatebirds. It takes experience to know what your electronics are showing you.

Weather Proverbs

Once upon a time, proverbs were the best an angler had, and knowing them gives you an edge on the weather, helping you plan your day, or in the case of bad weather, your escape.

Today, Sirius XM weather with satellite overlay on the chart plotter has been the savior of many billfishing captains. With it, anglers have plotted storms and decided where to pull up and run or stand pat and fish. Chapman Piloting and Seamanship lists a dozen weather proverbs, and they all have truth and can give an angler a broad feeling for the weather but not the snapshot now available.

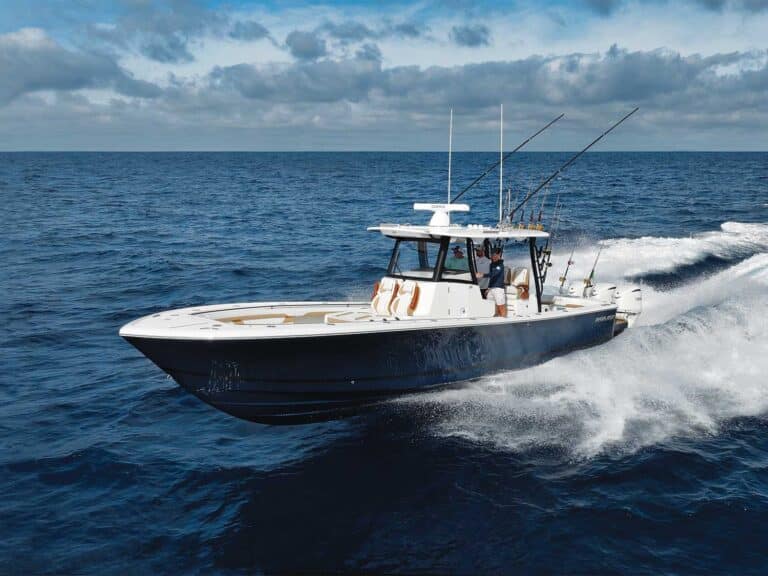

Barefoot Boat

I have a friend who calls the autopilot a mate with no bar tab. This system certainly does the boring part of getting the boat from port to the rip, break or seamount, but once there, it can make the crew more efficient by freeing up the skipper to hunt with his eyes or even assist in the cockpit.

Jason Roberts is a charter captain and an electronics installation technician who charters out of the Florida Keys but lives in Clermont, Florida. “I use autopilots all the time,” Roberts says. “So many times when I fish it’s a light crew, and we need everybody in the cockpit to work the lines, set baits and gaff fish. I’ll sure use the autopilot then, so we can step away from the helm, still maintain a lookout but keep the cockpit moving smoothly.”

Roberts often just sets a compass heading on the pilot and gets busy with the tackle. But he frequently relies on patterns that let him keep on the fish and his hands on the tackle. His favorite pattern is the cloverleaf. “When I fish the Cape Canaveral, [Florida], buoy, I can set the buoy near the center of my pattern and cloverleaf around it all day. You cover a lot of water and do it systematically.”

Burke has a different take on autopilot. He’s been fishing from the Keys to the Northeast since the early ’70s. When he’s fishing, he keeps the helm to himself.

“Say I’m trolling along, and I see a fish on my right outrigger,” he says. “He’s out there, hanging back, looking but not biting. I’ll make a turn toward that bait and slow it down, so it drops in the fish’s mouth. It often makes the fish bite.”

Soundings in the Dark

Soundings were few and far between on charts as late as 1950. Throughout the Pacific theater, subs charted waters accurately, and eventually, anglers benefited from that as well. In charts from the ’20s and ’30s, you can see soundings run in straight lines from about 20 or 30 fathoms toward the shallows — a clear sign pilots were making charts with a lead line.

Nowadays, we take sonar for granted, and with the advent of CHIRP, anglers are quick to abandon standard sonar. Burke says they might be acting too quickly. “The best captains are running their new CHIRP technology alongside the older systems, at least at first,” he says. “Think about it. You’ve been using a 10-degree cone for decades and learning to interpret the bottom and the fish in between based on past experience. You’ll learn to take advantage of CHIRP faster if you compare it to what you’re already used to.”