Special delivery: Sign up for the free Marlin email newsletter. Subscribe to Marlin magazine and get a year of highly collectible, keepsake editions – plus access to the digital edition and archives.

With the high cost of fuel these days, trimming your boat properly means you get the best-possible fuel-burn rate. Old-school trim tabs are standard on nearly all boats 16 feet and larger and are a must in order to make the proper adjustments in certain sea states, to not only maximize the ride, but also to get the best speed-to-fuel-burn ratios. Without them, trim needs fly out the window, often leaving you vulnerable to the constructs of Mother Nature.

Trim options used to be limited to flaps that either attached to the transom or laid in flush to the aft-bottom part of the hull, attached via a heavy-duty hinge. We adjust these flaps up and down with a switch that activates an actuator with either a hydraulic pump or an electric motor, allowing them to move up and down on command.

Tab Options

Two of the most common systems found in offshore-fishing boats of this style are Bennett hydraulic trim tabs and Lenco electromechanical trim tabs. While Bennett deals with mostly hydraulic tabs, it does offer both. Both of these trim-tab options angle down from hinges on each side, deflecting water as it rushes past the hull and raises the transom up on whichever side needs raising, and vice versa. The system is very simplistic yet uber-effective.

But boating technology continues to evolve—as it should—and lately, some builders have been installing a different style of trim tab called an interceptor. It is a fall-free, low-profile device that attaches to the transom of your vessel. Similar to standard trim tabs as it relates to the effect, an interceptor uses a blade that protrudes straight down to achieve trim and lift through the creation of hydrodynamic pressure.

These systems are fairly integrative and also have auto functions. If you plug in the proper information, the auto function can take the guesswork out of the equation and continuously trim the boat for you, while automatically adjusting to the sea conditions. Interceptors also claim to improve fuel economy and vessel speed, so choosing the right interceptor seems to come down to research. All brands offer custom interceptors that will work with boats that have prop tunnels.

While I have yet to personally make the switch from standard tabs to interceptors on my vessel, I do know quite a few boat owners and captains who have, and all report a slight increase in speed as well as fuel economy, making the interceptors appear to be a more efficient option than conventional trim tabs. However, I must admit that I am old-school and prefer manual tab adjustments, but I have used these interceptors on a boat outfitted with the Zipwake Dynamic Trim-Control System, and the automatic system did work rather well.

The Yin and the Yang

The main advantage of an interceptor system is a smaller profile, as well as the speed at which they go up and down. Interceptors move from fully retracted to fully extended in under 2 seconds, which is much faster than conventional tabs, which typically can take up to 10 seconds. The interceptor style is also very sensitive and requires far less throw to achieve similar lift to that of a standard trim-tab system.

However, there is always a stark juxtaposition when comparing technologies. One main disadvantage to the interceptors is that because of the small blades, they need strong water flow to be effective, meaning a solid rate of speed. A trawler, for example, cruising at 8 to 12 knots does not provide enough water to flow over the blades for them to create adequate lift. For boats like this, trim tabs with a larger surface area are going to be much more effective for trimming the hull. Otherwise, for any true planing-hull vessel, such as the hulls of sportboats, the interceptors are an effective option.

On the flip side of this advantage, it has been reported that interceptor blades can be bent at speeds greater than 50-something knots. And because the interceptor blades protrude straight down, the force on this blade at high speeds just becomes too much for it to handle. Standard tabs go down at a very shallow angle, so they can be used at higher speeds without the worry of them getting ripped off the boat. The tried-and-true trim tabs will get the job done and are fairly easy to install. And they also come with a smaller price tag than most interceptor systems.

Size, Power and Delivery

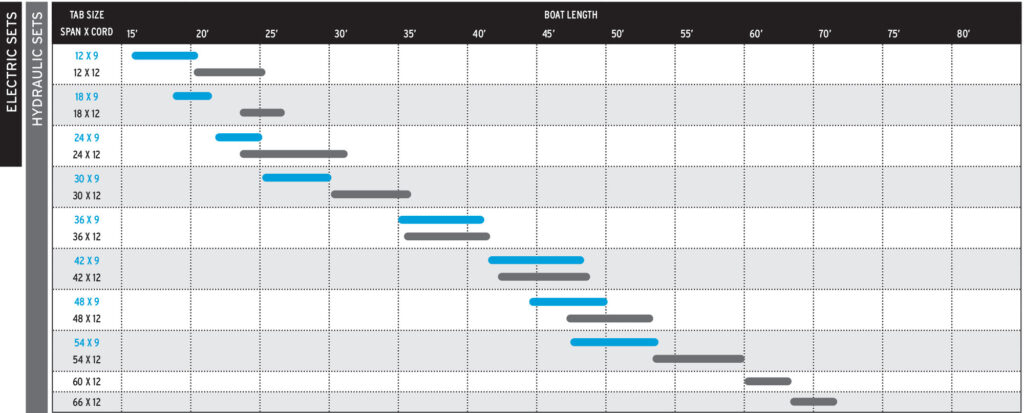

As a general rule, boats with top speeds of around 35 knots would require at least 1 inch of trim-tab span for every foot of boat length. For example, a 22-footer would use a 24-inch (span) by 9-inch (cord) tab on each side, according to Bennett Marine, which has a great guide that is quite helpful. For boats that go over 35 knots, it is recommended that a performance-style tab system be used over the standard style.

Durability is the biggest advantage of hydraulic over electric systems. The motor for the trim-tab system with a hydraulic unit is installed inside the boat in a dry environment. Hydraulic actuators do not rely on a seal where the shaft enters the cylinder body; instead, the seal is made on the piston face, inside the cylinder, where no marine growth can occur. If a seal on a hydraulic actuator should break, its replacement cost would be the inexpensive cost of the seal instead of the expensive cost of replacing an entire electric actuator.

For electric trim tabs, the electric motor is underwater inside the actuators, which places them in a position to have a higher probability of failure. The reason for this is that electromechanical actuators have shaft O-rings that keep this system watertight. All it takes is some marine growth on the actuator that can cut the O-ring seal, letting water into the system. When the shaft of the electromechanical actuator is extended out of the cylinder body, it creates a vacuum inside the actuator. When a vacuum is pulled underwater, this allows water to be sucked in. Once water enters the actuator, the boat will need to be hauled from the water and the actuator replaced.

Read Next: Check out Capt. Karl Anderson’s feature on handling close calls at sea.

Overall, electric actuators are easy to install and will get the job done, but I don’t recommend them on any boat that cannot easily be removed from the water. Smaller boats that live on trailers or lifts, or can easily come out, can get away with these because you can expect to be replacing your electromechanical trim tab more often than a hydraulic trim tab.