Reach into your bait freezer, grab five bags of small ballyhoo and a pack of mackerel, dip a bucket in salt water, plop the frozen yellow bricks into your bucket, admire your vast sticker collection, walk away, begin another task.

An hour later: Revisit the bucket, paw through the bricks (which are no longer bricks), rip open the bag, throw the empty bag on the deck, rig five-dozen swimbaits, align them neatly in your bait box, take pride in your fastidious work.

Listen to the captain yell, “He’s on the right dredge,” look at the angler as he grabs the mackerel pitch, press retrieve on your LP electric reel, watch as the blue marlin eats the pitch bait, taste the sweat as it drips from your upper lip, feel the cool water as it washes over the transom, smell the diesel from the whistling turbos, notice the tightness of your backhand wraps squeezing your hand, shield your face when breaking off the leader on the fish’s last surge skyward, rejoice over the first release of the day.

Of the ballyhoo you used in the last year, how many of them did you catch? Of that number, how many did you process? Don’t forget the dredge mullet, because you pitched to plenty of fish off that glowing orb. Oh yeah, that $2 million white marlin you caught? Or the unforgettable day in Guatemala where you went 37 for 43? What about the bonita belly you caught your personal-best swordfish on? According to just about anyone in our industry, bait — not just ballyhoo, all bait — keeps Earth spinning. Unfortunately, bait fall fatally victim to being included with those routine items we so often take for granted. Except for maybe Mark Pumo, the owner of Baitmasters of South Florida. I called him hoping for a little insight about a key component to our sport’s success.

A Window-Seat View

“Hey Austin. They [his bait boats] didn’t catch much, but we’re packing right now. If you can get here quickly, you’ll get to see a little bit of the action.” I take my phone from my face, which reveals the time: 8:58 a.m. Immediately, I imagine the nightmarish South Florida traffic. Mark asks, “Well, where are you coming from?”

“Fort Lauderdale.”

“Ah, damn, I was hoping you were staying nearby. If you can leave right now, I’ll tell my guys to wait for you to get here and pack the rest.” I-95 South, Friday, 9:27 a.m.

“Turn left onto NW 69th street,” my GPS yells. I weave through the Miami rush-hour traffic. Getting off at the correct exit isn’t of any concern to me at this point; I’m just trying not to get killed. My phone routes me through the notorious French neighborhood known as Little Haiti. It looks like no place I’ve ever seen in the United States: Each side street features brilliantly painted, ramshackle houses, and people laugh on the stoops of khaki housing-project buildings. Graffiti crawls up each and every structure. I pass a woman walking with a basket of laundry balanced on her head.

Striking cultural juxtapositions like those available in Miami always remind me that my life is full of luxuries both big and small; simultaneously, they horrify me because I take so many of those things for granted on a day-to-day basis. We all do, really.

A small, yellow sign reads Baitmasters of South Florida. The white door below it, which is receiving a fresh coat of paint, swings open. It’s 9:38 in the morning, and Mark invites me inside. For mid-January, it’s pretty hot outside. However, the continuous opening and closing of the minus-30 degrees F blast freezers keeps the inside of the Baitmasters facility cool. Organized chaos unfolds before me. Very, very organized chaos. In a beer flat, little nests of copper wire catch my eye: pin rigs. The employees work at dizzying speed with clear purpose. Each one knows exactly what to do and how to do it, fast. It becomes obvious that this level of productivity is pretty commonplace here. A man opens the office door and quickly introduces himself to me: “I’m Rey Valdes.” Rey seems like an important guy around here. He hands Mark a stack of papers — which he briefly scans — and then Mark disappears into the office.

“I saw a niche — a need, really — and knew I could produce a better product than what was on the market,” Mark explains. As he was in the process of giving me Baitmasters’ history, it started to make sense: Mark is actually a guy who seizes opportunity. The trite saying tends to lose its weight, but Mark literally embodies carpe diem. His “hurry up and get here” directed at me on the phone, his personal tenacity instilled into each individual employee, the fact that he couldn’t confidently go fishing when he was younger because of the total lack of quality baits — the puzzle started to fit together. It’s why, when I’m walking down the dock at Sailfish Marina, I see empty Baitmasters boxes piled high at every trash can. It’s why mates will rig a Baitmasters ballyhoo to fool a timid Atlantic sail. It’s why owners, captains and mates alike put everything on the line and pull his baits for big-money tournaments. And it’s exactly why this complex machine works.

“We Aren’t Popping Our Baits Out of a Mold”

“It’s a lot like farming, y’know — we — we aren’t popping baits out of a mold, we aren’t making them in a laboratory. We have to do the best we can with what’s out there — what’s available,” Mark tells me. The irony is that, before Baitmasters, Mark sold surgical instruments. He left the industry for a variety of reasons, chief among them: the “volatility of the medical market.” While harvesting a nonrenewable resource isn’t exactly a steadfast business model, Mark capitalizes on times when they’re catching.

“Over the years, we’ve developed all kinds of tricks and techniques to ensure the baits we get are processed in the best way possible, but it all starts with our boats. If the boats aren’t producing a good, quality ballyhoo from the right location, there’s nothing you can do to make that fish any better.” Mark looks, blankly, at the floor.

Daydream, Nightmare

“Austin, what the heck are you doing? Your right long is washed out!” I’d been dealing with this all day. I yell up the tower, not taking my eyes from the spread, “These baits are total crap!” If my stepdad taught me nothing else in my stint working on *Southpaw, it’s to appreciate good bait. We always caught our own. On off days, we spent hours in the backcountry, hair-hooking every single ballyhoo. We wanted baits with no scales missing. It never bothered me, because I knew they’d swim for hours. In the dead of summer, when catching greenbacks was all but a distant memory, when we’d go halfway to Cuba to find our clients a few schoolies, I’d anguish over the prospect of watching a blue marlin inspect a hideous blueback and laugh at it. Why risk that? Good thing is, we’d stockpile greenbacks when they were around, with hopes of our supply making it through the summer. Most times it did. A few days, though, we’d have to thaw a bag of baits we caught offshore.*

A Ballyhoo-to-Burgers Comparison

“You can go out and sink the boat with B-grade baits. It’s finding a steady supply of A baits that’s difficult,” Mark admits. Given the opportunity to talk with a bait savant, I asked him what the deal was with bluebacks and greenbacks. “They’re two totally different fish,” he continues. “Look closely, you’ll see they look nothing alike.” I started to feel like our charter clients who’d say, “Marlin? Those are the fish that look like swordfish, right?” Mark takes me to school: “Bluebacks have a red tip on their beak and a red tip on their tail, whereas greenbacks have a red tip on their beak and an orange tip on their tail.” Bluebacks also, he says, “have a bigger eye and are much shinier.” This raises a question, so, naturally, I interject, “Is it a dietary thing?” Sure is. Equate ballyhoo to beef you buy at the grocery store. Grass-fed is safer, tastes better and is more desirable but, in turn, more expensive.

Rey clarifies, “If their poop is solid green, the baits are grass-fed, and they’ll last much longer.” He adds, “The blue baits will gorge themselves on plankton, making the bellies decompose a lot faster; those baits will tear like butter when trying to put a hook in them.”

Mark, laughing, follows, “Yeah, eating plankton or hanging out at the local sewer outfall, which is no good.” If every single grocery store started selling only grass-fed beef, we’d grow accustomed to that quality. What would happen if those same grocery stores replaced high-quality meat with McDonalds hamburgers?

Reverence for the Resource

To say these folks have a profound respect for their crop would be a gross understatement. However, the pursuit of perfect baits puts a strain on all parties involved: Bait boats feel pressure to catch only greenbacks, and Mark has to develop the best possible processing tactics when those baits arrive, which, ultimately, drives the retail price up. “We’ve changed the industry by making the market accept only baits of a high pedigree,” Mark says. This means that Mark and his gang are at the mercy of the harvest. “The window to catch is limited; we have to be able to process as many baits as possible without neglecting the quality our industry expects.” Mark further says, “They’re a limited resource; we know we have to catch them when we can, process them when we can. This means our crew is basically on-call.”

I retort, “So you all aren’t working 9 to 5, Monday through Friday?”

He laughs, “If they catch on a Friday, we pack on a Saturday; if they catch on a Sunday and we have to drive down on a Sunday afternoon to pick up the catch — we’re there.” They will work until the catch is completely processed. You won’t ever hear “We’ll get to those tomorrow.” Mark explains, “We’re like bean pickers in here, y’know. We’re constantly sorting and sizing, and sometimes we’ll do 40,000 to 50,000 pieces in a day.” He adds, “That conveyor belt will run from 7 in the morning till 9 at night. We have to be ready for the fish. And when the fish come in, it’s all hands on deck.”

The Journey

A ballyhoo’s journey from flat to freezer at Baitmasters is a calculated, concise process. The simple thrust is: minimize the amount of time the fish are not frozen. They work with emergency-room urgency. When the fish are caught, Mark or Rey gets a phone call. The truck leaves their facility in Miami (at whatever hour it may be) and drives to Key Largo, where the fish are loaded onto the truck and driven back to Miami. After a swift unload, those fish are put into large containers of Magic Brine (I couldn’t pry the secret ingredients from him), where they sleep for the night. At 6 the next morning, the ballyhoo are pulled from the brine and tested for quality. First, Rey says, “We check the fish for overall softness.” If the fish fail to meet their standards, “We won’t risk it,” Rey says. They’ll declare soft, subpar baits “drift baits” for use on headboats targeting bottomfish. If the fish pass, they move forward to the next stage of processing. This, Rey justifies, “is where greenbacks really illustrate their value. A blue fish will fail every time — just fall apart.”

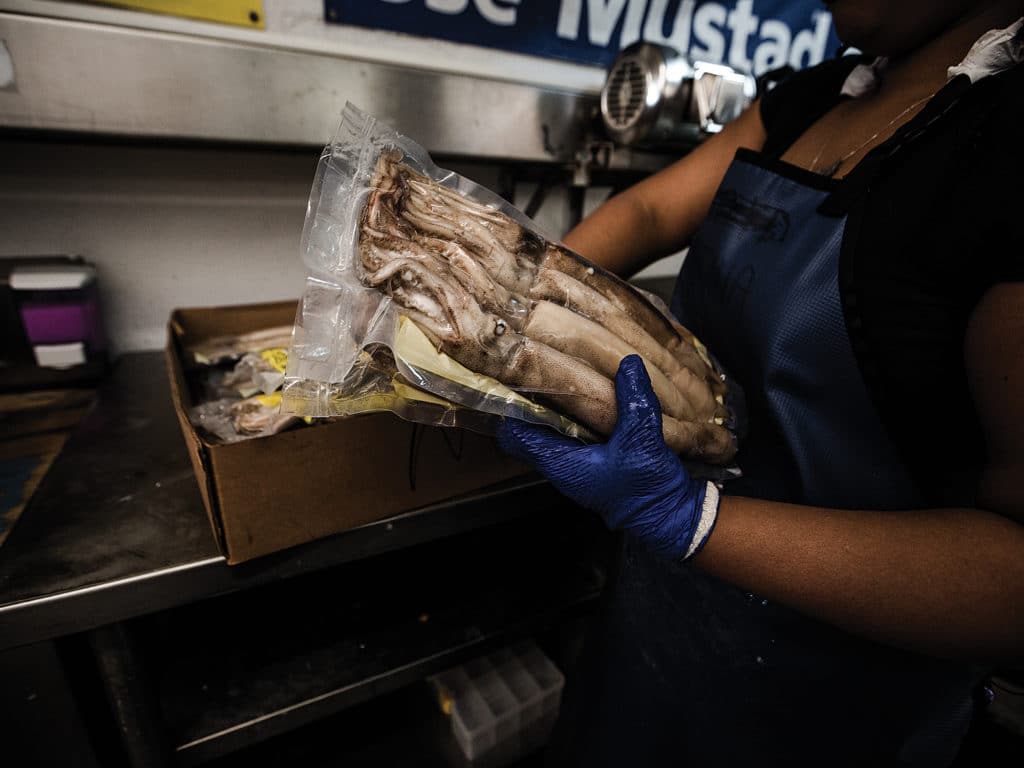

If the baits are deemed quality, they go back in the brine, with a little more ice added to bring the internal temperature of the fish back down. After a quick cool down, they empty the contents of the belly. From there, the fish are sorted by size: peewee, small, medium, large-medium, select, horse and jumbo. Down the line, the fish are bagged according to size and laid on the conveyor belt, where they travel to the vacuum packer. At the end of the line, the bags are taken to the blast freezers, where each bag will be frozen solid in nearly an hour. Rey says, “When they come out of the freezer to be shipped, we double check just to make sure the bellies and backs are hard as a rock.”

Into a LoBoy cooler with dry ice goes the bait; sealed, placed in a box, and off it goes. Simple, right?

“We Aren’t Just Sticking Fish in a Bag”

I asked Rey if he ever feels like their product is, perhaps, taken for granted: “People call me in the middle of the summer asking for 20 cases of smalls, and I say ‘We don’t have that,’ and sometimes their reply is, ‘Wha — what do you mean, you don’t have that?’”

Remember, they aren’t making bait from a mold. And while the greenback ballyhoo catch may be prolific, they aren’t always caught in the universally desired size. “Sometimes we only catch large-mediums.” Not everyone, everywhere has use for bait that size. The ballyhoo, mullet, squid, flying fish, mackerel, ribbonfish, eels — all of it — are a nonrenewable resource. “It’s a lot more than just sticking fish in a bag,” Rey says.

How dangerously easy is it for us, in our unique routines, to open a bag of ballyhoo, rig them with chin weights, drop them back, sancocho a Pacific sail, watch as a wahoo skyrockets on a long rigger and clips the bait off, and scream as a cunning white marlin slings our hook from its bill, just for us to wind it up and put another bait right back out there, without thinking twice? Before getting your paws on it, many faceless, nameless hands got that bait to you, in the condition you’ve grown to expect. Both macro- and micro-environments in our industry hinge on the presupposition that the baits we buy will a) be readily available at any time, and b) perform the way we want. It’s unnerving to think how easily we forget that bait is not a manufactured good. We want it, and we want it now — take my money!

Before hastily throwing the Baitmasters bag on your immaculate teak cockpit as you begin to rig 150 baits for your first fishing day off Isla Mujeres, Mexico, take a half-second to consider the amount of work put into each and every bait you use, that you never see.

About the Author

Austin Coit is a Florida-based photographer/writer who passed on his mate career to focus on telling the story a little differently.