If there’s anything I’ve learned from listening to a lifetime of fish stories, it’s that the best ones are often unbelievable yet totally true. I have also learned that, at times, what we leave behind is often more important than what we take with us.

The fish you’re trying to catch really has little do with the amount of enjoyment that comes from its capture. In fact, the physical catch itself often isn’t nearly as important—or as exciting—as the journey that led you to that moment. The finest novelist couldn’t describe most of the greatest moments of a fisherman’s career—not because elegant enough words don’t exist to paint the picture, but because fishing in its purest form is a feeling, one you can’t fake and one that can’t be taken away from you. Nor is it an action. Rather, it’s a mindset, a way of life—a primal vibration stored deep inside the human spirit that rises to the surface whenever our hands touch the rod at just the right moment. It is rarely completely understood by anyone other than the participants.

The term “fishing” is often confused by outsiders as being a hobby. An onlooker might view the cumbersome equipment found on a gameboat as nothing more than a wiggling stick one dances above a country stream. But in reality, the apparatus are extensions of who we are: a direct connection to nature and a direct line to our soul. A panfish captured on a stick and a piece of string can be as equally meaningful to a fisherman as landing a 1,000-pound marlin on a $2,500 state-of-the-art outfit.

Watch: Learn to rig a swimming mackerel here.

Every fisherman has a journey with individual goals to support that journey. We might enjoy parts of the adventure with others by our sides, but the most memorable moments are often shared alone. It’s the fish of a lifetime we release despite knowing we will never see it again. It’s the King of the Pond we spend years trying to capture, and in the moment we finally do, we quickly let it go to continue its reign. Here is where people often confuse the size of a fish with its true meaning and significance. And that is how I found my entire fishing life flashing before me, all because of a promise.

Remembering Scarback

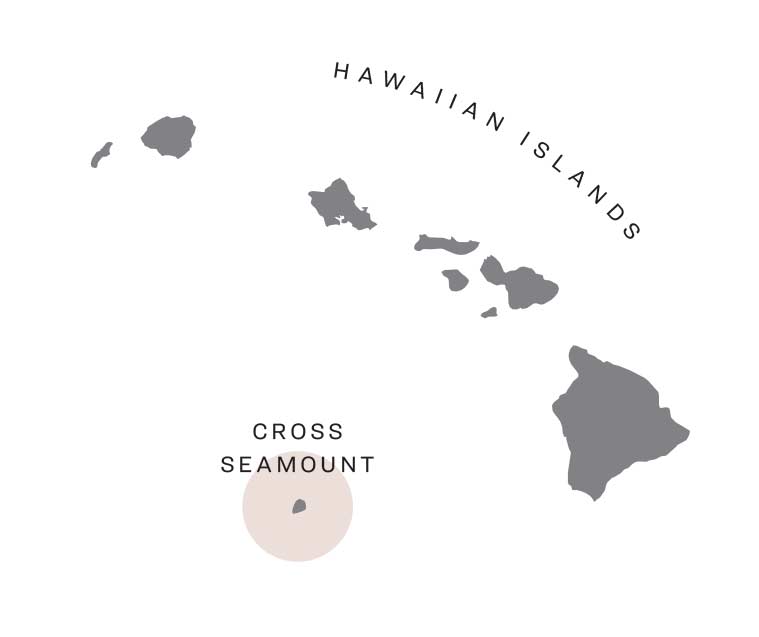

I believe that a blue marlin of unworldly proportions is put on this planet to humble even the largest of egos. Scarback took up a short residence on Hawaii’s Cross Seamount but retains a permanent residence in my mind. I would see her in all her glory for two trips in a row. This freak of nature was adorned with two giant scars across her back, looking as if she’d had a run-in with a boat and won. Every ounce of my soul wanted to say otherwise, but no part of me believes that a rod and reel could catch this wickedly awesome beast.

My first encounter with Scarback was impressive, and perhaps the most humbling of all my fishing experiences. We were working a huge pile of bigeyes—likely some 80 tons’ worth—that refused to bite. While it’s not unusual for fish not to bite, it is extremely rare to find such a big pile that doesn’t have a single willing participant. No matter how I drove on the school or what technique we used, they refused. We could see tuna swimming all around the boat, but they let the chum drift by—untouched.

Growing tired of the tuna charades, I decided to leave them in search of others. The funny part was that even though I wanted to leave them, they now refused to leave me. The school was following me everywhere I went. We call this “floating” or “walking the pile,” meaning that the tuna get locked onto your boat like they innately do to flotsam. It’s their natural desire and attraction to be around structure, and they followed me like a loyal dog.

An hour later, the tuna decided to throw the switch. Just as I took the first bite of my lunch, the danglers started to explode with a nice class of fish. Sixty- to 90-pound bigeyes were committed to hanging themselves on the 12-inch rubber squid suspended from the metal dangler bars, with total disregard for anything else. The tuna battled for the lures, none of which were more than 4 feet from the boat. The second we yanked a fish over the rail, another tuna would engulf the squid when it hit the water again. It was a sight, but it was nothing compared with what I was about to witness.

When I first saw the ominous black figure, I immediately said to the crew, “Great, whales—here we go again….” But as the shadow grew, so did my disbelief. Holy Mary, that’s a marlin, I thought.

“Look! Look, look!” I screamed aloud, unable to articulate anything more intelligible. The creature had everyone’s attention as it effortlessly inhaled a 90-pound tuna hanging on the back dangler just inches from the boat. The fish broke the 900-pound mono leader with little more than a slight ping.

The tuna suddenly skyrocketed around the boat. An even-more-awkward stillness followed; we continued motoring slowly down-sea. I just stood on the back deck, mouth open, trying to comprehend what the hell I had just seen. The fish was so radically big, I wouldn’t want to attach a number to it.

Then I made a rookie mistake: “Boys,” I said, “you will never see that again—never ever, ever, ever!” And just as I finished that sentence, the danglers unexpectedly erupted again. It seemed that the tuna had returned to feed, and we started catching them like nothing had ever happened. No part of me expected the tuna to return, and I didn’t think I’d ever see that marlin again. But, just as I pulled in a 60-pounder, I watched that magnificent fish come up and grab an 80-pounder so close to me that I reached out and tried to touch its massive dorsal fin.

The vessel shook like an earthquake as tunas bounced off the propeller blades, and my heart shuddered twice as hard. The beast ate another hooked tuna.

The first time, she revealed herself from the depths to show us how unbelievably powerful she was. Then, she showed us how calculated she could be: slowly and purposefully coming from behind. The tuna may have been in a panic, but she was not. And with a slight flick of her head, she gracefully swam off with that 80-pound tuna hanging out of her mouth like a dog with a bone.

As the biggest fish I’d ever seen disappeared, I thought how strange it was that I was really happy knowing some fish just aren’t meant to be caught; she was one of those fish. I wondered if even the most optimistic dreamers had ever thought they’d actually see one that big someday. I certainly did not.

Just Another Day

I took watch around noon as we approached the fishing grounds. I’d held the wheel through the night and slept away the early morning. The first thing I noticed when I awoke was that the lures weren’t in the water, despite the sun being up for hours. I grumbled something like: “What? Are you guys all rich now, just out here yachting?” The crew looked at me with confused smiles as I grabbed a couple of my standard rigged jets, but the lures looked as haggard as the women I generally take home after last call. Well, that’s not going to work, I thought, I’m way too sober to be seen with these things hanging around the boat.

Another search of my bag produced two pretty ladies. One was a brand-new chrome jet head that shone like the top of the Chrysler Building, and the other a triple-skirted black-headed bullet that Jonah Marks gifted to me before going to Australia.

Cowering from the heavy spray, I ran out on the deck barefooted and hurriedly set the lures. Disgusted, I found myself soaked from head to toe, running back into the cabin to towel off and go about my daily onboard yoga routine. Twenty-five minutes passed when I found myself in a distorted downward-facing dog staring at the spread.

Something is going to eat that bullet, I thought, as it dish-ragged down the Pacific swells. No sooner had the thought crossed my mind did I witness the most mind-blowing head-and-shoulders marlin bite—and to this day, the only one I’ve ever watched upside down.

The overly committed bite was absolutely radical; her initial run was legendary as the old Penn Senator screamed, throwing a 6-foot cloud of dried salt around it. Every time I thought that the fish was done jumping, she jumped again, and again. It was breathtaking. The water exploded around her like she was setting depth charges, thrusting her massive head out of the water, seemingly running on her giant pectoral fins, and even the turbulent seas seemed tranquil compared with her chaotic fight display.

I cranked on the smoking reel for as long as I could before it became obvious that if I didn’t drive on this fish, we were going to get spooled.

It was an endless standoff. Despite turning and chasing the fish, we were going full noise and couldn’t get an inch of string back on the reel. I stared out my driver’s-side window at the monofilament-to-Dacron splice for what seemed like forever (the GoPro would later reveal that “forever” was 13 minutes), watching a splice that would not move; even though the boat was belching soot and giving it everything it had, the fish insisted on swimming up-sea.

My crew did an awesome job, from cranking like champions to wiring and handling the fish boatside. She was a big, absolutely gorgeous fish. Beautifully proportioned—every bit a thousand pounds—and massively thick all the way to her tail. She’s a proper one, all right—even perfect—and the biggest blue marlin I’ve ever caught on rod and reel. It wouldn’t be hard to argue that her snooter would have looked awesome on my desk at home, but I told the boys to put the gaffs away.

“No gaff?” one of them asked.

“No gaff,” I answered.

“No kill, no keep?” they asked in unison.

“No, boys, it’s too big to keep,” I said, putting my foot down. As an outsider looking in, you’d think I was totally insane. And my crew’s faces showed it.

The universe has a funny way of testing us sometimes. I could only laugh: Of course the next marlin I caught would be this one.

A Promise

Just days prior to this experience, my eldest son, Kanyon, and I were talking. As the conversation progressed from one topic to another, he eventually uttered the words: “You should let big marlin go, Dad, so I catch them someday.”

I stood contemplating this request: Was it even possible that the ocean’s big marlin were destined for extinction as my son approached his best fishing years? While I seriously doubted it, I said what any devoted father would: “How ‘bout this, buddy? I’ll let the next big marlin I catch go, just for you.”

“Great idea, Dad!” he exclaimed.

In that moment, a promise was made, and I was destined, not only as a father but as a man of my word, to keep it.

Read Next: Build a tournament-winning team with these tips.

I grabbed the leviathan’s giant baseball-bat-like bill, remembering the promise I made to my son. I struggled to hold on as she pinned my body to the covering board: my ribs compressed, my diaphragm aching, and my breathing labored. I mentally noted that a journey of nearly 20 years took two hours and 14 minutes to complete. I had envisioned this moment countless times: while jogging, standing in line at the bank, staring out airplane windows, even while making love. But none of my dreams could prepare me for how it would feel to reach the climax of my marlin-fishing career.

There was no conflict, sadness or remorse. Before the promise, there were never any questions—not a single doubt about killing the beast before me. My greatest fantasies included my children, who would be there to celebrate in some sort of tribal family ritual. I would share her flesh with my friends, drink beers at the dock with her bill slung proudly over my shoulder. It was supposed to be the greatest day of my life, but that’s not how it felt at all. Sometimes there is something more powerful in knowing you could do something but make a conscious decision not to, more power in letting it be rather than killing it. That power was a promise.

Emotional Aftermath and Letting Go

So, I let the big fish go, patting her giant head, telling her she’d better thank a little boy named Kanyon. Strangely, the old soul seemed to acknowledge my suggestion with a giant slap of her tail as I tipped my lucky hat’s tired visor in a prolonged nod, as if to say in a slow, Southern drawl, “Well, thank ya, ma’am,” as she swam away.

Again, I found myself with the same strange feeling that some fish weren’t meant to be captured. Even though this was supposed to be my turn—my moment—it was bigger than that. Even though I was supposed to take her life, fulfill my bloodlust, balloon my ego and quell my desire, I didn’t. It just wasn’t my time to join the past legends on that old Grander Wall in downtown Kailua-Kona.

I emotionally shook off the previous 20 years of want, and it began to feel oddly warm and fuzzy. What had changed?

For most of my career, I’ve measured my self-worth by what the scale read. How many tons of tuna could I put on the auction floor? Or how many pounds of marlin could I string up by its tail? An endless quest of fish has afforded, and continues to afford, me loads of fun, and at times, a lot of money. But I never went fishing for the money; I went for the indescribable feeling that is fishing. I went to connect with nature in the only way I know how. I’ve lived life as a square peg in a world full of circular holes, often uncomfortable and socially awkward, so I went to sea to fill a void that seemed patchable only with salt water. I fished, because no matter how hard things ever got onshore, I knew that there was a place past the horizon reserved just for me.

It takes many years of experience and vast amounts of pride swallowing, but when you are finally able to grasp that these beloved creatures are truly more beautiful in their own environment—wild and free—doing what they were put on Earth to do, that is the moment when you honestly discover the meaning of the word “love,” the meaning of a promise kept.